Booking: The shareholder friendly OTA king

You can listen to the Deep Dive here

Booking’s modern identity as a dominant, European-centric travel aggregator obscures its chaotic origins as a quintessentially American dot-com darling: Priceline.com. The original company, founded by Jay S. Walker, launched in 1998 as Priceline.com. It was built on a strange, patented mechanism called “Name Your Own Price”.

This model was a form of reverse auction, meaning consumers bid a price for a service, like a hotel or flight, without knowing the specific brand until after the purchase was complete. The concept cleverly targeted the perishable inventory of airlines and hotels, which have a marginal cost of essentially zero for an empty seat or room. The model allowed suppliers to offload this excess inventory at a discount without cannibalizing their primary, price-transparent distribution channels. While revolutionary, as you can imagine, the model was built on a foundation of psychological friction.

Despite this inherent friction, Priceline.com became a high-flyer of the internet bubble. I mean if you look at numbers for Priceline back then, you would legitimately wonder “friction? what friction?”

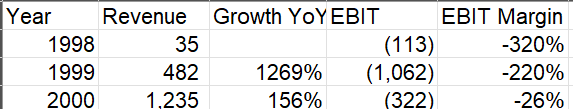

After starting the priceline.com service on April 6, 1998, the company reported $35 million revenue in 1998. Next year’s revenue? $482 million. The year after that, revenue was $1.2 Billion. If you are shocked to see how AI startups are scaling revenues, it looks like this is pretty much what happens when you are in the early phase of a true technological transformation!

If this is what happens in the early phase of transformation, let’s pray (!) that we can skip the middle phase in AI. Priceline was smart enough to go public in March 1999 and by May of 1999, its market cap exceeded $20 Billion. Of course, tech bubble popped next year and to make matter considerably worse, 9/11 almost seemed like a death blow to them. Market cap went below $200 million by December 2000!! From a tech bubble darling, Booking actually became a penny stock. So, the company had to do a 1 for 6 reverse stock split.

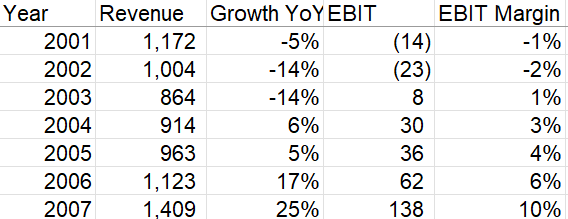

What perhaps surprised me more is how long it took Booking to exceed their revenue in 2000. It’s one thing for the stock to experience ~99% drawdown after a bubble, but it really puts things in perspective when you see it took Booking SEVEN years to exceed their revenue in 2000! Despite internet being obviously a truly revolutionary technological phenomenon and Booking being one of the winners, their fundamentals (not just stock price) weren’t immune from a long suffering!

This period, however, forged the company’s core competency: resilience. The management team that survived the dot-com abyss was immediately tested again by the 9/11 attacks, followed by the SARS-1 outbreak in 2003. Booking’s current CEO Glenn Fogel did a recent interview with Stratechery in which he indicated the battle-hardened, pragmatic culture was perhaps the most valuable asset to survive the crash. It created a leadership team that was unsentimental about its original, failing business model and actively searched for one that actually worked.

The search for that new model led Fogel, then in charge of the company’s small European operation, to an uncomfortable conclusion. The “Name Your Own Price” model just didn’t make sense in a European market where low-cost carriers like Ryanair and EasyJet already offered transparent, rock-bottom prices. Fogel realized “Name Your Own Price” can only be a niche market and to pursue the larger opportunity, Priceline needed customers to offer a platform that allowed the customers to see the price and exactly what they were getting. This search led Priceline to acquire a small UK-based company called Active Hotels in 2004 for $161 million, and, in 2005, a small Amsterdam-based outfit named Booking.com for $133 million. These acquisitions, which barely registered compared to the 1999 IPO valuation, would become the most important strategic decisions in the company’s history.

Active Hotels and Booking.com operated on a completely different framework known as the “agency model.” At the time, the dominant US player, Expedia, used the “merchant model,” where it bought rooms from hotels at a discount and then resold them, capturing the margin. This model was good for Expedia’s cash flow, as it collected the customer’s money upfront, but it was not as good for hotels, which had to be paid later. The agency model, in contrast, was bit of a godsend for hotels, particularly the small, independent properties that dominate the fragmented European market. Hotels simply listed their rooms, and the customer paid the hotel directly upon arrival. Booking would then send an invoice to the hotel after the stay to collect its commission.

This model was operationally superior for rapidly scaling inventory, as it required zero risk or complex integration from the hotel. But it was less than ideal for Booking. Booking.com was an early and aggressive user of search engine marketing, paying Google for traffic. This created bit of a cash-flow paradox: Booking had to pay Google for ad clicks upfront, in cash, but would not get paid its commission from the hotel for months. As Fogel explained, “The faster you grew, the worst your negative cash flow can get worse, worse, worse, worse, worse.” As a result, Booking.com was the perfect acquisition target for a cash-rich, publicly traded company like Priceline, which could inject the capital needed to solve this working-capital crisis and unleash the model’s explosive potential.

For the next decade, the small European acquisition proceeded to completely eclipse its American parent. The agency model, fueled by Priceline’s capital and basically a scientific approach to Google advertising, became an unstoppable engine of growth. The original “Name Your Own Price” business became a rounding error. By the mid-2010s, Booking.com accounted for the vast majority of the group’s revenue and growth. In, 2018, the company acknowledged this reality by officially changing its corporate name from The Priceline Group to Booking Holdings.

After the topsy-turvy first decade in the public market, Booking also matured into an incredibly well run, scalable marketplace in the internet! It’s hard to even “see” GFC in their numbers as the business just kept growing topline at higher than 20% every year between 2008 and 2014 (although some of these growth was inorganic in nature) while increasing operating margins from 15% in 2008 to 36% in 2014.

Of course, the pandemic was a major hiccup and, Booking was a laggard in recovering from the pandemic because their higher booking mix was geared towards what the pandemic crushed and took longer to recover: hotels, cross‑border Europe, short urban stays, and business travel. Nonetheless, their 2025 revenue will be ~75% higher than 2019 revenue, exhibiting yet again the resilience of their business model.

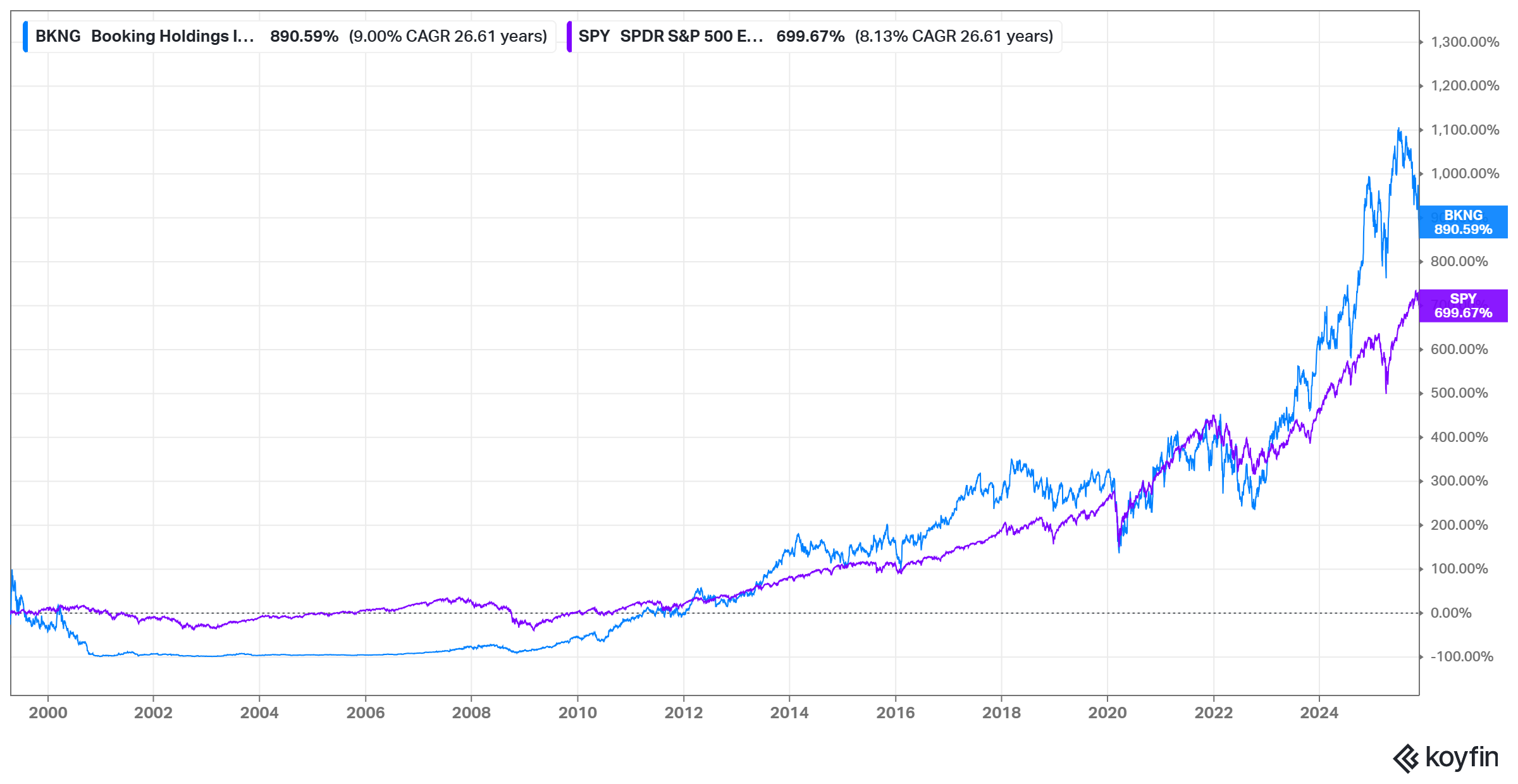

Today, Booking is a ~$155 Billion market cap company and despite IPO-ing during the super hot tech bubble period, Booking still managed to generate a respectable ~9% CAGR over the last two and half decades. And if you’re one of the lucky ones to bottom tick the stock after it crashed, it was almost a 1,000-bagger!

Booking pivoted from “Know Your Own Price” to “Agency” model to “Merchant” model while navigating a frenemy relationship with the 800 pound gorilla named Google and responding effectively to the Silicon Valley’s favorite: Airbnb. That is some rich history! 🫡

But how does Booking travel from the status quo to the future where AI may re-write a lot of assumptions in how we choose our destinations?

Before I explore such questions, let’s first deepen our understanding of the status quo of the business. The rest of the Deep Dive will be behind the paywall.