Tariff conundrums, AI capex boom, Edge computing fallacy, AI ARR chicanery

A Programming Note: A couple of you have given me the feedback that instead of generic title of the Daily Doses, I should mention the topics covered in the title/email subject. As you can see, I have decided to implement it from today.

Tariff conundrums

While there was a broad consensus that higher tariffs will lead to price increases, the evidence so far has been largely mixed. Last month, Wirecutter mentioned that they tracked 40 Wirecutter picks over two months and prices of two-third of those products didn’t change at all (three, in fact, went down and the prices of the rest ten did go up).

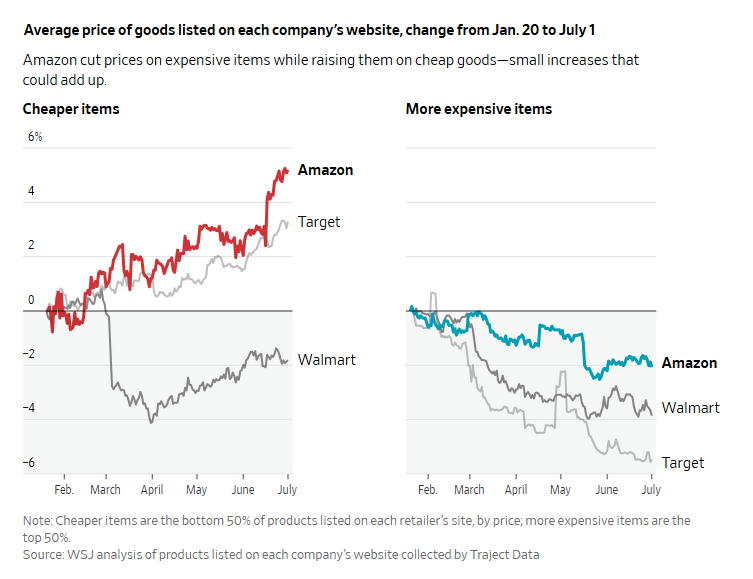

Yesterday, WSJ published a report that looked into ~2,500 items and compared the price changes from January 20 to July 1. Interestingly, their analysis found that on an aggregate basis of the sample, Amazon did raise price by mid-single digit percent for cheaper items whereas it actually decreased prices for more expensive items. There are perhaps many ways to look at this data, but I wonder if a good interpretation is that tariffs are much easier to pass through to consumers for basic necessities. The fact that prices for more expensive items declined may be more of a factor of demand softening for consumer discretionary items.

Of course, Amazon has millions of SKUs. An analysis looking at even 2,500 items may not be representative of overall data, so I am not sure I want to extrapolate too much here. Earnings calls of these retailers in the next couple of weeks may be more instructive of overall impact from tariffs.

AI Capex Eating Everything?

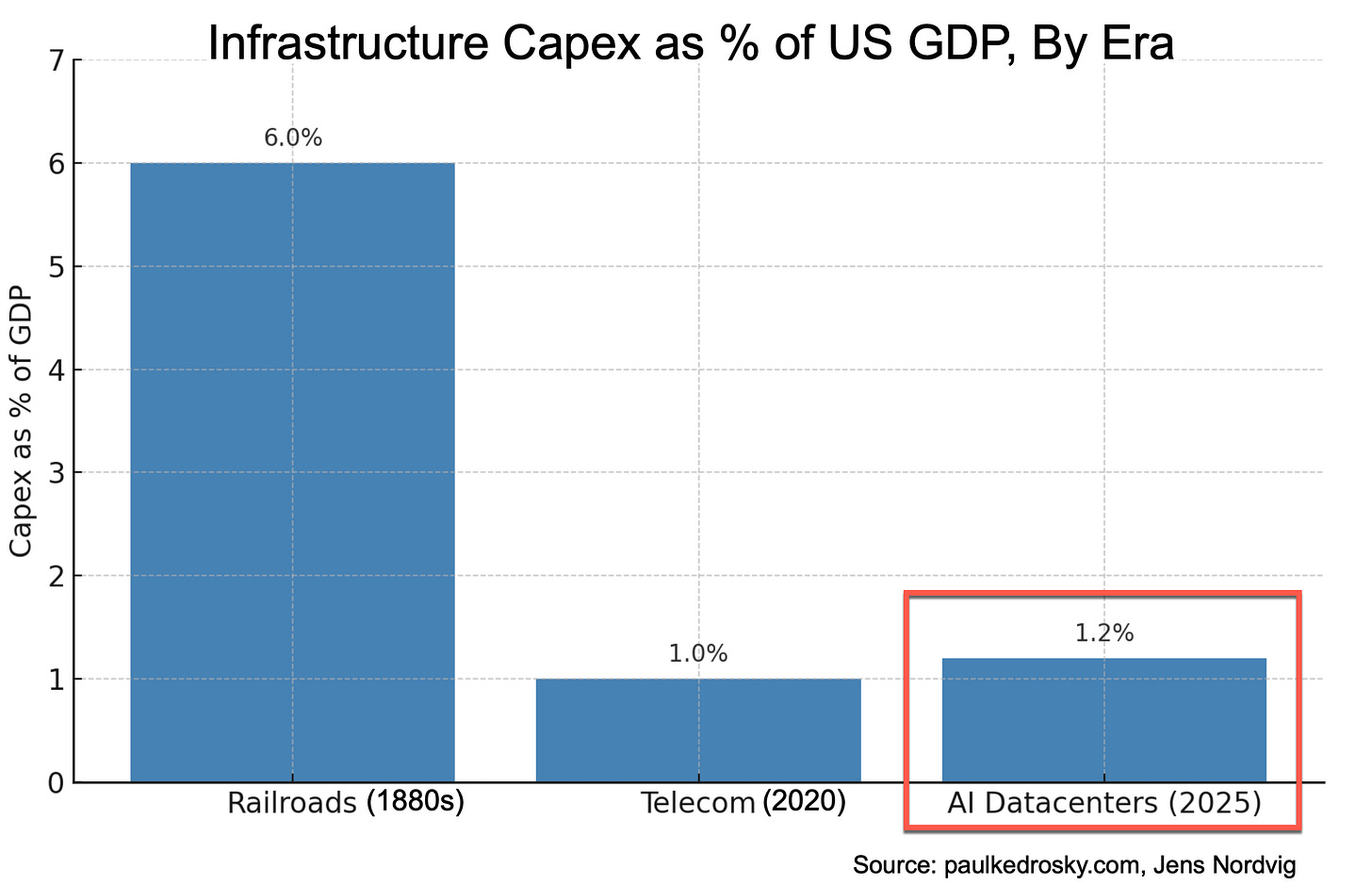

Paul Kedrosky put the scale of AI capex in context in his piece “Honey, AI Capex is Eating the Economy”:

Compare this to prior capex frenzies, like railroads or telecom. Peak railroad spending came in 19th century, and peak telecom spending was around the 5G/fiber frenzy. It's not clear whether we're at peak yet or not, but ... we're up there. Capital expenditures on AI data centers is likely around 20% of the peak spending on railroads, as a percentage of GDP, and it is still rising quickly. And we've already passed the decades ago peak in telecom spending during the dot-com bubble

Kedrosky has an ominous tone about this capex boom and even lamented the possibility that investing in such “rapidly depreciating technology” may be diverting fund from other productive areas in the economy. I find the argument that this investment rush is "starving" other sectors to be overstated; the primary funders are a handful of cash-rich technology giants reallocating enormous internal profits, a different dynamic than a broad-based diversion of capital across the entire economy.

He also made the point that while railroads were century long investments, these AI capex is basically a red queen’s race. That analogy also seems to miss some critical differences between the two capex booms.

Railroad expansion was a physically-constrained, sequential process where economic value was unlocked incrementally with each mile of track laid over decades. In contrast, today’s megacap tech companies are layering AI capabilities onto pre-existing digital distribution networks with billions of users. The output of this new AI datacenter infrastructure, e.g. a better algorithm, a new feature, a more efficient ad model can be deployed globally and almost instantaneously via software. Therefore, while he is correct that these are "short-lived, asset-intensive facilities" unlike "century-long infrastructure", the timeline to generate decent revenue from the investment is radically compressed from decades to potentially a couple of years. Nonetheless, the size of the capex relative to historical parallels is an interesting data point worth highlighting.

In addition to "Daily Dose" like this, MBI Deep Dives publishes one Deep Dive on a publicly listed company every month. You can find all the 61 Deep Dives here.

Prices for new subscribers will increase to $30/month or $250/year from August 01, 2025. Anyone who joins on or before July 31, 2025 will keep today’s pricing of $20/month or $200/year.

Edge computing fallacy

It’s much more commonplace to hide the opinions that turn out to be (at least temporarily) incorrect, so I appreciate this piece by Nilesh Jasani self-reflecting why his thesis around edge computing didn’t play out as anticipated. But let’s remind us why edge computing had so much appeal in the first place. From Jasani’s piece:

In late 2023 and early 2024, the promise of edge computing was not a niche technical idea; it was a palpable hum of excitement. The logic was clean and compelling. Moving artificial intelligence to the edge would solve the technology’s most pressing problems.

First, there was privacy. Processing data on your own device meant it never had to travel to a server owned by someone else. Your secrets would remain your own. Second was latency or annoying delays. With the thinking done locally, responses would be instantaneous, a crucial feature for everything from conversations with voice assistants and augmented reality to autonomous vehicles. Finally, there was cost and access. Why rent time on a remote supercomputer when your own device could do the work? This would democratize AI, making it reliable even without a perfect internet connection.

So, what went wrong?

The edge‑computing dream fizzled when the headline devices e.g. Humane’s AI Pin, Rabbit R1, Qualcomm‑powered “AI PCs”, and even flagship phones failed to run meaningful models locally and instead routed most “on‑device” features back to the cloud, exposing a gulf between marketing and reality. At the same time, scaling‑law breakthroughs made ever‑larger models dramatically more capable, spurring megacap tech companies to build colossal training clusters that intensified the data‑center’s gravitational pull and undercut the economics of decentralization. These cloud‑resident “agentic” AIs now orchestrate tasks on our gadgets from afar, leaving phones and PCs as sleek terminals and proving that narratives about privacy, latency, and cost cannot beat the brute‑force advantages of centralized compute.

Follow-up on AI ARR chicanery

I would like to have a quick follow-up on my Daily Dose from July 20. I mentioned this interesting quote by Replit’s CEO:

It's very easy in AI to increase ARR while users are not happy because they're spending a lot more and like not getting the results and in some cases maybe shouldn't grow that fast because like you'd want users to get a better experience for less less money and so it's one thing that we try not to obsess.

As it turns out, there may be some historical parallels to this phenomenon. Marc Andreessen wrote this piece as a tribute to Steve Jobs back in 2024, but the following bit stood out to me:

If you had enough sales and marketing hype, or used enough FUD—Microsoft like IBM before them, was famous for pre-announcing products that weren’t even on the drawing board, to freeze the market—you could bluff your way through to market success while your product wheezed along.

One of the things that went wrong in Silicon Valley in the 1990s—and one of the things that caused the crash in 2000—was too many Valley companies bought into that approach. So you had too many Valley companies that launched into market too fast and shipped subpar products. A lot of the products people used in the dot-com era, especially business products, were used out of fear—the fear of being left behind. Then 2000 and 2001 came around and everybody collectively said, “Holy Lord, these products are all crap.” And they all got dropped overnight, in many cases killing their companies.

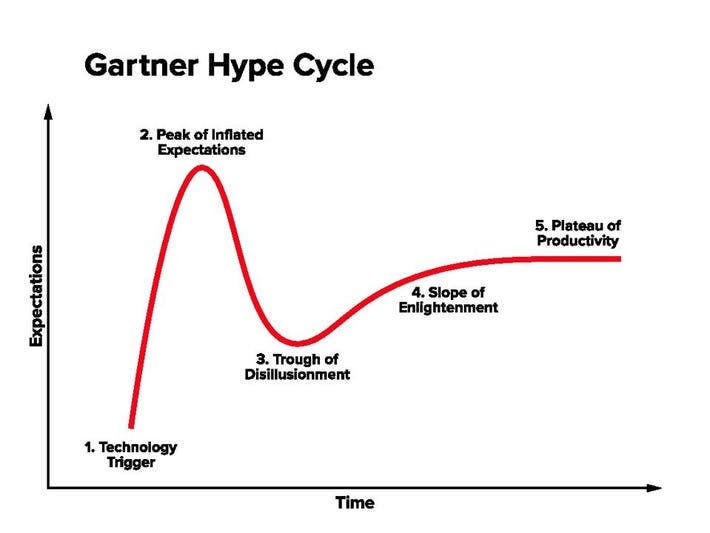

We really perhaps need to maintain two opposing ideas in our head at the same time. AI is revolutionary and is likely the most transformative technology of our time. Yet, it will also probably destroy (and create) a humungous amount of wealth. And we will be in various part of the hype cycle along the way. One thing is certain: we are definitely NOT in the “trough of disillusionment” part of the cycle.

Current Portfolio:

Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.