The Power, Peril, and Plight of The Big Tech

Please subscribe to receive future posts

Democrats and Republicans may not agree much on most things, but they both have expressed their desire to curb the power of the big tech through brute force of regulation. Senator Warren published her concerns and expressed the desire to break up Google, Facebook, and Amazon (Apple was included later) in a Medium blog back in March 2019. President Trump, on the other hand, has mostly focused on big tech’s alleged bias against conservatives. It is not just the presidential candidates, but there seems to be a growing bipartisan consensus on this issue. Even regulators have started making the move by fining record fees against Facebook and initiating discussions on antitrust investigations against Google and Facebook. Considering the bipartisan consensus as well as the impending 2020 election, the debate on big tech will continue to flood the headline and political rhetoric which can possibly weigh on the stock prices.

My objective in this report is to outline the complaints against big tech, and the counterarguments from the big tech against these complaints. But before delving into those discussions, it is important to have a brief discussion on how antitrust interpretation has evolved over last fifty years in the US, and what lessons we can draw from antitrust case against Microsoft in the late 90s. Finally, I have outlined some suggested remedial actions regulators can undertake against big tech, and what antitrust litigation may possibly mean for the shareholders of the big tech.

Please note that there is a wide range of opinions when it comes to antitrust concerns and while I will make inferences based on readings from both sides of the arguments, reasonable people can possibly end up with different conclusions. At the end of the day, antitrust is a legal concern, and I am a generalist. Antitrust related discussion also tends to be very academic in nature and from my readings, I can sense that you can easily come up with ten different PhD dissertations on this very topic. I will primarily wear the investors hat and will try to avoid “analysis paralysis”.

For the nature of this report, I will primarily summarize, and may resort to somewhat reductive statements, but I will leave enough sources (hyperlinked) so that readers can explore on their own if they want.

Full disclosure before you start reading: I own Facebook, Amazon, and Google in my personal portfolio. Given that I also own Berkshire Hathaway, I have indirect exposure to Apple. My interest in the discussion on antitrust primarily stems from my portfolio’s significant exposure to big tech, and I wanted to develop a reasonable understanding on the topic of antitrust as I suspect this topic is not going away anytime soon. It’s good to remember the possible biases I may have while you read my report.

Section 1: Chicago School vs Economic Structuralism

In 2016, Lina M. Khan published “Amazon’s Antitrust paradox” in The Yale Law Journal. Even though it is a 96-page paper, it became viral, and helped drive many of the arguments we have been hearing on big tech regulation. Khan discussed and contrasted the approach taken by the economic structuralism, also known as Structure-Conduct-Performance (SCP), and Chicago school (more recent) when it comes to antitrust in the US and attempted to make a case of antitrust litigation against Amazon. The title of her paper itself insinuates to the seminal paper by Robert Bork titled “Antitrust Paradox”. Khan is a critic of Chicago school philosophy and has been advocating to broaden the scope of antitrust from Chicago school’s (or Bork’s) “consumer welfare” narrative to focus more on market structure.

Broadly speaking, economic structuralism focuses on how concentrated market structures promote anticompetitive forms of conduct. The philosophy promotes policing not just for size, but also for conflicts of interest, especially in vertical integration within a market. The Chicago school, however, is of the opinion that the objective of antitrust should be to maximize consumer welfare, best pursued through promoting economic efficiency. While economic structuralism was the traditional philosophy accepted in the court up until the 70’s, Chicago school has dominated and upended the scope and interpretation of antitrust regulation over the last 40 years.

Contrary to popular belief though, consumer welfare is not interpreted as just lower prices. The present interpretation of antitrust law includes both present and future consumers who “may lose from high prices or indirectly through a limitation of choices of variety and quality of by retardation of innovation process”. Although Khan criticizes the doctrine of “consumer welfare”, she herself admits consumer welfare does go beyond just “lower prices” and she also seems to think Amazon can face antitrust litigation even under existing antitrust framework.

Even though economic structuralism has seemed to gain momentum, especially among politicians in recent times, I find it unlikely that the “consumer welfare” narrative will be trumped in court anytime soon since giving away with such narrative will likely have much broader and deeper implications even beyond the big tech, given many other industries are also concentrated these days. Economic structuralism tends to define market rather narrowly as evidenced by United States v. Pabst Brewing Co. in which the govt. wanted to undo a merger between 10th and 18th largest beer company in the US because the combined market share three years following the merger increased from 23.95% to 27.41% in Wisconsin. The govt’s argument was increased concentration is harmful for competition, but the court ruled the definition of the market as too narrow. It’s not just the size, but vertical integration also used to be much more scrutinized as it was the case in Brown Shoe v. United States even though the shoe manufacturer and retailer had only 4.0% and 1.2% market share. The main concern was the conflict of interest that may arise from the integration between manufacturer and retailer.

Looking at how concentrated and vertically integrated many of the industries have become, I believe economic structuralism is somewhat dated under the economic reality of the twenty-first century. I think it is highly likely that antitrust litigations will end up focusing on consumer welfare and will perhaps concentrate on broadening the scope of the definition of “consumer welfare”. Given no drastic change in court’s antitrust philosophy is likely and considering the relevance and similarity of antitrust case against Microsoft, I believe Microsoft is much more instructive than Standard Oil and/or AT&T, which were among the most high profile antitrust cases in the US in last century.

Section 2: Microsoft’s decade of antitrust

As I was going through Microsoft’s antitrust saga, it is perhaps impossible not to feel a bit of déjà vu. Many of the allegations against Microsoft seem still very relevant against the current crop of big tech and therefore, I believe Microsoft’s antitrust case is the go-to event to speculate how the probable litigations against big tech may play out.

Microsoft’s flirtations with the regulators started in 1990 and it took them almost twenty years to get the monkey fully off its back. I have created Microsoft’s antitrust timeline below with the help of these two WSJ and Wired articles. From alleged anticompetitive behaviors, and blocked M&A to court order of Microsoft’s break up (and eventual reversal), this case had it all. While the venom of the antitrust litigation died down in October 31, 2001 in the US, and December 22, 2004 in EU, the case was completely closed on April 27, 2011, marking the end of Microsoft’s 20-year court battle with the regulators.

I have provided Microsoft’s return and the index return in the chronology outlined below. The returns are calculated from the previous event to the current event. Of course, beyond the antitrust concerns there were many external factors that drove the return of the stock and therefore, this is not indicative of event-driven impact on the stock. More robust event-driven research will be discussed in section 5. The shaded areas in the table are more prominent events in this decade long saga.

Section 3: The laundry list of big tech’s sins and possible counterarguments

In this section, I will summarize the major allegations against the big tech, and counterarguments are discussed simultaneously. Please note this is not an exhaustive list of complaints against big tech.

Extremely concentrated market share

The big tech is inarguably powerful companies with high market share in their respective markets. Washington Post wrote, “Google and Facebook Inc. together controlled 60% of mobile ad revenue and 51% of digital ad revenue globally in 2018, according to eMarketer. In the U.S., Apple Inc. has about 45% of the smartphone market; about 47% of all U.S. e-commerce sales go through Amazon.” However, as per the current interpretation of antitrust law, the plaintiffs need to establish that defendant: “a) possessed market power; AND b) willfully acquired or maintained this monopoly power as distinguished from acquisition through a superior product, business acumen, or historical accident”. Therefore, even if a company has 100% market share, it may not be illegal under US antitrust law. Any attempt to monopolize a market is also illegal, but here the plaintiff needs to prove that the defendant: “a) engaged in predatory or anti-competitive conduct, AND b) there was a “dangerous probability” that the defendant would succeed in achieving monopoly power.”

Moreover, it can be tricky to define the market and make a case that a company possesses market power even for some of the big techs. Take the example of Amazon. Benedict Evans tweeted the following series of tweets: “Amazon has ~50% of US ecommerce. E-commerce is ~10% of US retail. People who worry about Amazon generally talk a lot more about the 50% share than the 5%. But, the reason to worry is the scope for it to take over a lot of the rest of physical retail, not just ‘ecommerce’. The reason to worry about Amazon is the threat to Walmart and Macy’s and Target and Kroger and every other physical retailer. But if that’s your worry, then Amazon has 5% market share. Conversely, if you say it has 50% share, you’re saying it only competes with eBay and Etsy. That is, there’s a sort of Catch 22 here: If you’re worried about it, it has 5% market share. If you’re not worried about it, it has 50% market share.”

To be fair, while the press has been touting the high market share to imply something incriminating, the pro-enforcement intellectuals are generally aware of the limits of this argument, and they focus more on allegedly anti-competitive, predatory pricing, privacy/data security or some other questionable practices to pin the blame on the big tech.

Predatory pricing

Predatory pricing was one of the major allegations against Standard Oil in the early twentieth century. Of the current big tech, the allegation of predatory pricing is primarily directed at Amazon and hence, the following discussion is perhaps only relevant for Amazon.

Following the decision to break up Standard Oil, subsequent courts cited the decision and mentioned “price cutting became perhaps the most effective weapon of the larger corporation.” However, the courts distinguished between competitive advantages drawn from superior skill and production, and those drawn from the sheer power of size and capital, which courts determined to be illegitimate. Over the years, there is a new dimension called “recoupment test” added to the predatory pricing discussion. Here I am quoting Justice Kennedy on this issue in 1993: “ Evidence of below-cost pricing is not alone sufficient to permit an inference of probable recoupment and injury to competition… Without recoupment, even if predatory pricing causes the target painful losses, it produces lower aggregate prices in the market, and consumer welfare is enhanced.” Therefore, for predatory pricing to be incriminating, the plaintiff “must demonstrate that there is a likelihood that the predatory scheme alleged would cause a rise in prices above a competitive level that would be sufficient to compensate for the amounts expended on the predation, including the time value of the money invested in it.” The recoupment test has instituted a high bar for predatory pricing to be incriminating since predatory pricing rarely passes this test.

Amazon was accused of predatory pricing when it introduced Kindle, the e-reading device in 2007. Bezos allegedly not only sold the Kindle device at below manufacturing cost (perhaps an example of “razor and blades” model) but also priced the bestseller e-books at $9.99, significantly below the range of hardback prices between $12 and $30. However, govt. concluded no wrongdoing since in aggregate, the e-books segment was profitable for Amazon. Khan, however, finds this problematic: “this perspective overlooks how heavy losses on particular lines of e-books (bestsellers, for example, or new releases) may have thwarted competition, even if the e-books business as a whole was profitable. That the DOJ chose to define the relevant market as e-books—rather than as specific lines, like bestseller e-books—reflects a deeper mistake.” I find this argument unconvincing because the definition of the market seems deliberately narrow and chosen in a way that would fit Khan’s intended outcome. Khan also discusses why the requirement of recoupment test can be extremely challenging to prove Amazon’s predatory pricing: “it may not be apparent when and by how much Amazon raises prices. Online commerce enables Amazon to obscure price hikes in at least two ways: rapid, constant price fluctuations and personalized pricing. Constant price fluctuations diminish our ability to discern pricing trends. By one account, Amazon changes prices more than 2.5 million times each day. Amazon is also able to tailor prices to individual consumers, known as first-degree price discrimination. There is no public evidence that Amazon is currently engaging in personalized pricing, but online retailers generally are devoting significant resources to analyzing how to implement it.” Challenges such as these will only increase the already tall bar of proving predatory pricing in court. However, given the novelty of the challenge, the court may not take a rigid approach to the “recoupment test” when it comes to big tech. It is important to note that practices such as constant price fluctuation and price discrimination are not unique to Amazon; other retailers undertake these practices as well.

Anti-competitive behavior

Anti-competitive behavior is perhaps one of the most pervasive complaints against big tech. Since the nature of the complaints vary, I have discussed these issues separately for Google, Apple, and Amazon below:

Google: Google has been accused of favoring its own content over competitors in its search results. It was fined €2.42B by European Commission in 2017 for biasing the search result, and fined another €4.34B later in 2018 for requiring “manufacturers to pre-install the Google Search app and browser app (Chrome), as a condition for licensing Google's app store (the Play Store)”. Interestingly, the US FTC in 2013 decided not to pursue charges against Google for the same alleged conduct. Even the legal considerations taken by both authorities were strikingly similar which imply that it is perhaps the difference in antitrust philosophy that led to opposite outcome. Based on the decisions, it can be inferred that EU is of the opinion that “governmental intervention is appropriate to protect (“order”) the process of market competition and does not depend on a showing that a particular form of allegedly anticompetitive conduct is likely to generate a net negative welfare effect.”

In its decision, FTC explained why it did not pursue the “biased search” allegation against Google: “A key issue for the Commission was to determine whether Google changed its search results primarily to exclude actual or potential competitors and inhibit the competitive process, or on the other hand, to improve the quality of its search product and the overall user experience. The totality of the evidence indicates that, in the main, Google adopted the design changes that the Commission investigated to improve the quality of its search results, and that any negative impact on actual or potential competitors was incidental to that purpose. While some of Google’s rivals may have lost sales due to an improvement in Google’s product, these types of adverse effects on particular competitors from vigorous rivalry are a common byproduct of “competition on the merits” and the competitive process that the law encourages.”

DoubleClick (acquired by Google in 2007) founder Kevin O’Conner made similar point in an op-ed at WSJ: “To be sure, Big Tech’s market dominance can have negative consequences for smaller firms. I can cite two firsthand experiences. In 2009 I co-founded FindTheBest, a company that sought to help consumers compare their options in fields from health to education to business. Each month we helped more than 30 million people find the best investment adviser, graduate school or even dog breed for their particular needs. One day our traffic dropped by half. Why? Google rolled out a new search algorithm. We never complained when Google sent us search traffic free, but boy did we howl when they took that traffic away. Was Google targeting us? Highly unlikely. Sorting through trillions of webpages to match billions of user queries remains an incredibly hard problem.”

Moreover, some research shows that Google’s search results show “bias” only in minority of search results and its competitors, in fact, are even more biased: “Google references own content in its first results position when no other engine does in just 6.7% of queries; Bing does so over twice as often (14.3%).”

Apple: Both NYT and WSJ recently published articles alleging Apple of biasing search results in its Appstore to favor its own apps over competitors’. While NYT found Apple prioritized its own app first in only ~1% of the overall keywords queried, WSJ mentioned their analysis showed “The company’s apps ranked first in more than 60% of basic searches, such as for “maps”. Apple denied these allegations and indicated users often search apps they have already installed in its Appstore to open the apps. If someone has already an Apple app installed, it makes sense to show the user the installed app first instead of showing other apps.

Apple also mentioned it uses 42 factors in its search ranking but keeps the methodology private primarily to prevent manipulation by fraudsters who may want to game the search results. The four factors that are most important are downloads, ratings, relevance, and user behavior (most important of these four) which is defined as “the number of times users select an app after a query and also download it”. However, NYT mentioned how the search for “podcast” and “music” showed wildly different result in last few years with Apple drastically favoring its own apps over competitor apps. Apple responded: “search for “the podcast app” ranked its own Podcasts No. 1 due to “user behavior data” in the U.S. In the U.K., The Podcast App (competitor app) ranks No. 1”.

Some argue Apple has its own incentives to not discriminate third party apps over its own app since it earns ~30% fee for third-party apps (only for paid apps e.g. many games, free-apps with in-app purchases e.g. Skype/TikTok, free apps with digital subscriptions e.g. Pandora, Hulu etc, and cross-platform apps e.g. Dropbox, Minecraft etc.) whereas it does not charge anything for its own apps. But the critics argue Apple biases the results to incentivize third-party developers to advertise the apps for keyword searches. There are also some controversies regarding 30% fee which critics consider as “tax” paid to Apple. Spotify, the competitor music app, filed an antitrust complaint against Apple on this 30% “tax” in March this year. Spotify did not allege Apple to manipulate the search results. Apple gave a strong reaction to Spotify’s complaint: “A full 84% of the apps in the App Store pay nothing to Apple when you download or use the app… The only contribution that Apple requires is for digital goods and services that are purchased inside the app using our secure in-app purchase system. As Spotify points out, that revenue share is 30% for the first year of an annual subscription — but they left out that it drops to 15% in the years after.”

One of the counterarguments against “biased” search results is supermajority number of apps are “branded” which means “someone heard about your app or your company somewhere other than the App Store”. According to a research, 100% of top 10, 90% of top 50, 86% of top 100, and 60% of top 400 downloaded apps are branded. This perhaps indicates even if search results are perfectly neutral, one needs to be a good marketer anyway to gain traction in Appstore.

Amazon: Amazon Marketplace has become a major source of controversy in recent times. Critics point out the conflict of interest in selling third party products and offering Amazon’s own brands at the same time. Thanks to Amazon’s popularity to consumers, despite the apparent conflict of interest, third-party sellers have flocked to Amazon in last 20 years. From 1999 to 2018, Amazon’s own share of the products dropped from 97% to 42%.

I initially found the crux of the critics’ argument somewhat perplexing. Sears started its own Craftsman and Kenmore brands as in-house brands in 1927. Sears was also selling third-party products and it certainly knew what was selling well. Walmart or any major superstore in the US has similar strategy. Amazon, however, differs from the physical superstores in at least two important ways. Firstly, unlike the superstores, Amazon has limitless shelves, and secondly, the data it collects from customers is vastly superior from the superstores.

Khan in her Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox wrote, “It is true that brick-and-mortar stores also collect data on customer purchasing habits and send personalized coupons. But the types of consumer behavior that internet firms can access—how long you hover your mouse on a particular item, how many days an item sits in your shopping basket before you purchase it, or the fashion blogs you visit before looking for those same items through a search engine—is uncharted ground. The degree to which a firm can tailor and personalize an online shopping experience is different in kind from the methods available to a brick-and-mortar store—precisely because the type of behavior that online firms can track is far more detailed and nuanced.” Therefore, even though fundamentally the business models are not different from what physical superstores do, Amazon’s business model is just better in some respects.

Another major complaint against Amazon is the presence of illegal or unsafe products, which was recently highlighted by WSJ. WSJ “investigation found 4,152 items for sale on Amazon.com Inc.’s site that have been declared unsafe by federal agencies, are deceptively labeled or are banned by federal regulators”. To fight against the counterfeits, Amazon has launched “Project Zero” in February, 2019, and has ramped up its litigation efforts against counterfeiters. As part of Project Zero program, Amazon says, “brands provide key data points about themselves (e.g., trademarks, logos, etc.) and we scan over 5 billion daily listing update attempts, looking for suspected counterfeits.” Moreover, if a brand identifies a counterfeit listing, they can remove it using a self-service tool (without needing approval from Amazon). However, I doubt Amazon will ever be in a situation when their success rate will be 100%. But it is intuitive to understand it is in Amazon’s best interest to make sure counterfeits do not harm consumer experience, and they have incentives to make this right for customers. Of course, even a low failure rate can lead to drastic consequences for some consumers in which case press and regulators can continue to mount pressure on Amazon.

Impeding innovation, and competition through rapid acquisitions

Google and Facebook receive a lot of flak for this. However, all big tech companies are “sinners” when it comes to acquiring startups. Here’s the run rate of acquisitions (sourced from Wikipedia) for five big tech companies: Apple (108), Microsoft (242), Google (227), Amazon (101), and Facebook (79). It is interesting to see how Microsoft has hardly been mentioned in the current big tech antitrust debate even though it too grapples with almost all the challenges other tech companies deal with. For example, as mentioned earlier, Bing’s search results were found to be more biased than Google. It also owns LinkedIn which is “monopoly” in online professional networking platform (arguably narrowly defined market, but that didn’t save other big techs from criticism). Microsoft also simultaneously operates and competes on a platform (e.g. Microsoft Store). It remains the undisputed leader in productivity software market, and operating systems market. And of course, it is one of the largest companies in the world right now in terms of market cap. Therefore, if anyone is concerned with size, it is almost inconceivable not to mention Microsoft at all. My sense is if the big tech indeed faces antitrust litigations, Microsoft will also eventually go back to its familiar courtroom battle after being largely left alone for last ten good years. Even if regulators do not focus on them at first, Microsoft’s competitors are likely to lobby hard to make sure Microsoft does not remain unscathed for too long.

Critics point out the antirust case against Microsoft helped companies such as Google and Facebook to emerge. This is also espoused by Elizabeth Warren and Roger McNamee who is a very vocal critic of Facebook. However, Microsoft did give an acquisition offer of $24B to Facebook in 2010, as did Yahoo ($1B in 2006), Google, The Washington Post, Viacom, MySpace, NewsCorp, NBC, and AOL. As Mark Zuckerberg reminded every potential acquirer “Facebook is not up for sale”, it remains a standalone company. After failing to acquire Facebook outright, Microsoft and Google both competed for a stake at Facebook in 2007, and Microsoft was successful in taking a stake. To do that, it valued Facebook at $15B in 2007, a level of valuation that was, in fact, source of ridicule at that time. While Microsoft did not make any offer to Google, Google did try to sell the company to Yahoo twice: first for $1M in 1998 (yes, that’s a million), and then for $5B in 2005. As Yahoo balked at Google’s price tag, it did not end up buying Google. There seems to be many such historical quirks that led to the tech behemoths we see today, and I think the tech critics try to create a grand narrative which seems to make intuitive sense but falls short after further scrutiny.

The more important question is whether the rise of rampant acquisitions impedes innovation and creates disincentives for entrepreneurs to start companies. A recent research indicates, in fact, the opposite as the authors “found evidence of a strong positive association between VC investments and lagged M&A activity, consistent with the hypothesis that an active M&A market provides exit opportunities for VC companies and therefore incentivizes them to invest”. Without exit opportunities, a strict antitrust law may lead to some unintended consequences and can possibly reduce VC funding for startups.

Critics also argue the big tech has created a “Kill Zone”, which consist of business areas “not worth operating or investing in, since defeat is guaranteed”. One of the most often cited example in this case is Quidsi, an online retailer founded in 2005, which was elaborately discussed in the book “The Everything Store”. Khan also accused Amazon of using predatory pricing tactics when Quidsi’s Diapers.com took off. However, despite Amazon’s aggressive pricing tactics, by 2010, Diapers.com outcompeted Amazon four to one in terms of Diaper sales. Amazon ended up acquiring Quidsi for $545M in 2010 and Quidsi entrepreneurs, Marc Lore and Vinit Bharara, made $400M more than their capital invested. While Khan implies Quidsi’s acrimonious relationship with Amazon, it turns out Quidsi also got a competing and better offer from Walmart. The founders allegedly chose to sell it to Amazon since they consider Jeff Bezos “The Sensei”. However, the Bezos charm seemed to have worn off rather soon. Marc Lore left Amazon to launch a new rival online retailer Jet.com in 2014. In just two years, he managed to sell Jet.com to Walmart for a whopping $3.3B in 2016. He still leads Walmart’s online retail business. The whole story makes me question the supposedly “impossible to entry” narrative. Quidsi founders basically found two successful rival online retailers in just last ten years and made a fortune at it. While Amazon is the Goliath in the story, it eventually killed Quidsi in 2017 as the company failed to make money. Amazon is indeed the loser in this case.

Khan made another accusation which, if established, perhaps will lead to stricter regulation. Khan mentions “By observing which start-ups are expanding their usage of Amazon Web Services, Amazon can make early assessments of the potential success of upcoming firms. Amazon has used this “unique window into the technology startup world” to invest in several start-ups that were also customers of its cloud business. It is possible regulators can ask Amazon to create a firewall to address challenges such as this. While FTC has already used firewall as an effective remedy in earlier occasions, DOJ’s view is somewhat inconsistent (pro-firewall during Obama era but anti-firewall during Bush and Trump era) . But given political and potentially public support, firewall can perhaps be more acceptable remedy going forward.

Free speech issue and other concerns

In the interest of keeping the report short, I will not discuss privacy or data security issues. Facebook has already been fined $5B by FTC in July, 2019 and in response, Facebook has been ramping up its efforts on privacy and data security by investing $3.7B in 2019. In fact, Facebook seems eager for more regulation, but critics also argue regulations such as GDPR has negative effects on startups and can end up firming the big tech’s competitiveness even further. However, I think it is perhaps more likely to see regulations such as GDPR being implemented more widely, and regulators may tweak some conditions to make the regulations less cumbersome for startups.

Conservatives primarily accuse Facebook and Google (or most of Silicon Valley) of having political bias against conservatives. In a three and half hour podcast of Jack Dorsey (Twitter CEO), Vijay Gadde (Twitter Global Head of Legal), Tim Pool (YouTuber/Journalist), and Joe Rogan (Podcast host), Mr. Dorsey seemed to acknowledge it is possible that they may have some liberal bias primarily because of “echo chamber” challenges within their own organization, but they are intent on addressing the free speech issue head on and would invite more inclusive input while formulating rules for their platform. Interestingly, I am also seeing increasingly more and more liberals accusing social media companies to prop up conservative media outlets in social media platforms. As a result, this has become a political mudslinging contest. Recently, political advertisement has also been a source of controversy for Facebook. Even though political advertisement is “single digit percentage” of total ad revenue in 2018, Facebook has been unwilling to consider total ban on such ads on its platform on free speech ground.

Roger McNamee in his book “Zucked” repeatedly mentioned how Facebook has installed a “filter bubble” through which people are not being exposed to broader spectrum of ideas. I think he underestimates how “filter bubble” is an inherent component in every human society, as evidenced by, for example, a very high probability of parents and children following the same religion. Moreover, I came across a research while reading the book “Everybody Lies”, internet websites, in fact, provide the highest probability (45.2%) of meeting someone with opposing political views compared to coworker (41.6%), offline neighbor (40.3%), family member (37.0%), and friend (34.7%).

However, I do think McNamee’s views on how free speech has become more troublesome in outside US has a lot of credibility to it. Facebook found itself in the hot water because of the atrocities committed against Rohingyas in Myanmar, and the rise of misinformation can be troubling for countries who have not been exposed to internet culture. Facebook has increased its fact-checking efforts, but as a user of Facebook, I do not think it is possible to eliminate harm in Facebook or any other social media platform. To illustrate the level of difficulty, let me quote McNamee from Zucked, “Facebook told Motherboard that its AI tools detect almost all of the spam it removes from the site, along with 99.5% of terrorist related content removals, 98.5% of fake account removals, 96% nudity and sexual content removals, 86% graphic violence removals, and 38% of hate speech removals. The numbers sound impressive but require context. First, these numbers merely illustrate AI’s contribution to the removal process. We still do not know how much inappropriate content escapes Facebook’s notice. With respect to AI’s impact, a success rate of 99.5% will still allow five million inappropriate posts per billion. For context, there was nearly five billion posts a day on Facebook…in 2013.”

Therefore, given the volume of the posts, even a tiny rate of failure of AI can lead to negative consequences for a lot of people. Facebook will have to continue to invest in manual and human-centered process, in addition to leveraging AI to address these issues.

Section 4: Suggested remedies to thwart the big tech power

First things first, despite calls for break up, I think breaking the big tech into pieces is an unlikely scenario. The difficulty of breaking these companies can be illustrated by this piece: “Facebook developed its technology stack in-house to address the unique problems facing Facebook’s vast troves of data. Facebook created BigPipe to dynamically serve pages faster, Haystack to store billions of photos efficiently, Unicorn for searching the social graph, TAO for storing graph information, Peregrine for querying, and MysteryMachine to help with end-to-end performance analysis. The company also invested billions in data centers to quickly deliver video, and it split the cost of an undersea cable with Microsoft to speed up information travel. Where do you cut these technologies when splitting up the company?” Microsoft’s example was also indication that the court is unlikely to call for break up. However, while the big tech is likely to be able to save itself from being broken up, it is perhaps a near certainty they will face increasing regulation in coming days. To navigate these impending regulations, I have looked into Khan’s suggestions for remedies (she primarily talks about Amazon), and Chicago Booth Stigler Center’s recent committee report on “Study of Digital Platforms Market Structure and Antitrust Subcommittee” which was led by Fiona Morton, one of the most prominent pro-enforcement scholar. Here are some regulations suggested by Fiona Morton and the rest of the committee.

The Stigler Center committee called for the creation of a Digital Authority (DA) akin to regulators in other sectors such as banking, and communications (FCC). The DA could a) have the authority to define bottleneck power (a situation where consumers primarily rely upon a single service provider, which makes obtaining access to those consumers for the relevant activity by other service providers prohibitively costly), b) set pro-competitive rules on data, and c) partner with antitrust agencies. If a company is found liable for violating antitrust laws, DA can enforce remedies such as: a) data sharing: “The relevant data to share may not be just historical data, but present and future data also”; b) Full protocol interoperability: “In a social media context this would allow the users of the new service to see not only all the content on their own service, but also content from friends on an incumbent site that was subject to an interoperability requirement”; c) non-discrimination: The incumbent cannot have different rules for own complementary services and third parties; d) unbundling: Incumbents can be prohibited from tying or bundling multiple services. Given these are not default operational guideline rather than “punishment” for violating antitrust regulations, it is not unlikely, in my opinion, that such regulations can be pursued by the government.

Lina Khan, on the other hand, suggests two different approaches when it comes to Amazon and other platforms: “Key is deciding whether we want to govern online platform markets through competition, or want to accept that they are inherently monopolistic or oligopolistic and regulate them instead. If we take the former approach, we should reform antitrust law to prevent this dominance from emerging or to limit its scope. If we take the latter approach, we should adopt regulations to take advantage of these economies of scale while neutering the firm’s ability to exploit its dominance.”

If government wants to promote competition, Khan suggests abandoning the recoupment test in cases of below-cost pricing by dominant platforms. Khan advocates a presumption of predation when a platform holds greater than 40% of market share in any local market. To address vertical integration, she suggests in addition to monetary threshold, regulatory agencies should “automatically review any deal that involves exchange of certain forms (or a certain quantity) of data.” She also asked to consider a stricter approach of separating platform business. I find these suggestions highly unlikely to be implemented as I have discussed in earlier sections, it would require a significant change in court Philosophy when it comes to antitrust.

If government wants to regulate platforms, Khan floated the idea of considering these platforms “public utility” as she considers Amazon as “essential infrastructure across internet economy”. This would be a monumental task for the government legal team to pull off, especially given thin evidence to prove this.

Section 5: Antitrust and shareholder return

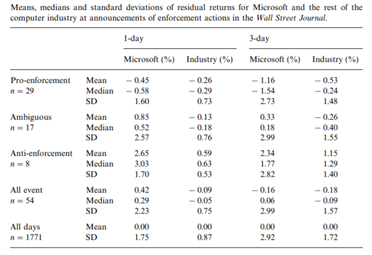

In antitrust cases, it is not just government, but other private companies/competitors, of couse, can also file for antitrust case. In fact, the ratio of private to government brought cases is ten to one in the US. On the other hand, in the EU, the decision to prosecute is largely left to public authorities. A 1995 research indicated that antitrust litigation resulted in 0.6% loss of firm value for the defendant and 1.2% firm value gain for the plaintiff. Considering the nature of potential antitrust charges against the big tech, Microsoft’s case is perhaps far more relevant. Microsoft’s case is encouraging for the current shareholders of big tech as an event-driven (1991-97) analysis (see below image) showed -0.58% 1-day median return on Pro-enforcement news, and +3.03% 1-day median return on anti-enforcement news. Moreover, for the pro-enforcement news events, instead of generating off-setting gains for Microsoft competitors, the mean loss to the competitors exceeded $1B per event, implying the cost of these litigations can be much broader than intended. Nonetheless, I think the political narrative has decidedly shifted and given the changing public perception, I think it is highly likely that at least some members of the big tech, if not all, are likely to face antitrust charges against them within next few years. Looking at how things have unfolded for Microsoft, shareholders may not need to panic in such a development.

Final words…

As a shareholder of the big tech, I think I would not be terribly disappointed if the regulator goes after all the big tech at once. These companies, in aggregate, have more financial muscle power than “God”, and they all have enough room in balance sheet to drag this as long as you can possibly imagine. If Microsoft’s case is any indication, the case could continue for multiple decades. I would be far more concerned if regulators decide to go after on one/two companies and ignore the rest. A razor-sharp focus on one company can be more likely to be successful from regulators’ perspective. In any case, the outcomes of any antitrust case can be treacherously path dependent which inherently relies on so many variables that can easily boggle any human mind.

Therefore, this is a final reminder that my inferences are not going to be rigidly held, and I am going to adopt a bayesian framework while following antitrust developments going forward.

Thank you for reading. Please subscribe to receive future posts in your inbox.