Amazon's Ambition in Groceries: Part 1

Back in 2023, Terry Smith from Fundsmith wrote the following as their rationale to exit their position in Amazon (emphasis mine):

Relatively new CEO Andy Jassy enunciated some principles of investment which investment projects had to have, namely:

1. Be big and capable of delivering good returns on capital.

2. Serve an area of the market in which consumers are not already well served.

3. Amazon had to have a differentiated approach to competitors’ and

4. Amazon had to have or be able to acquire the competence to execute.

Our view was that there was a lot to like about that statement, and it gave us some comfort in purchasing a stock we had shied away from before. However, it is always easier to talk the talk than it is to walk the walk and the CEO’s pronouncement that he wanted Amazon to seek routes to get bigger in grocery retail ran counter to all these principles. In our view grocery retail has none of these characteristics and Amazon has already stubbed its toe in this sector with the Whole Foods acquisition.

Moreover, our recent experience of engagement with companies which we believe are making capital allocation and other mistakes has produced a much longer list of those who have ignored us than of those who have listened and so we are likely to be more active in exiting such situations where we disagree with the manner in which our investors’ capital is being allocated. Where companies choose to invest outside a powerful core franchise in which they already have expertise we believe they are likely to destroy value, and especially so where they are entering a sector which already has poor returns.

While it is hard to know, my guess is many Amazon shareholders (including me) perhaps largely agreed with Mr. Smith that Amazon’s big bet in groceries is bit of a headscratcher but likely chalked up Smith’s decision to exit Amazon as missing the forest for the trees. However, I recently came across a data point that startled me a bit and persuaded me to spend some time understanding the grocery market. My objective is to better understand Amazon’s bet in groceries. While understanding Amazon’s bet on groceries is ultimately my objective, today’s focus is not about Amazon. It is about Walmart and their decision to get into grocery business.

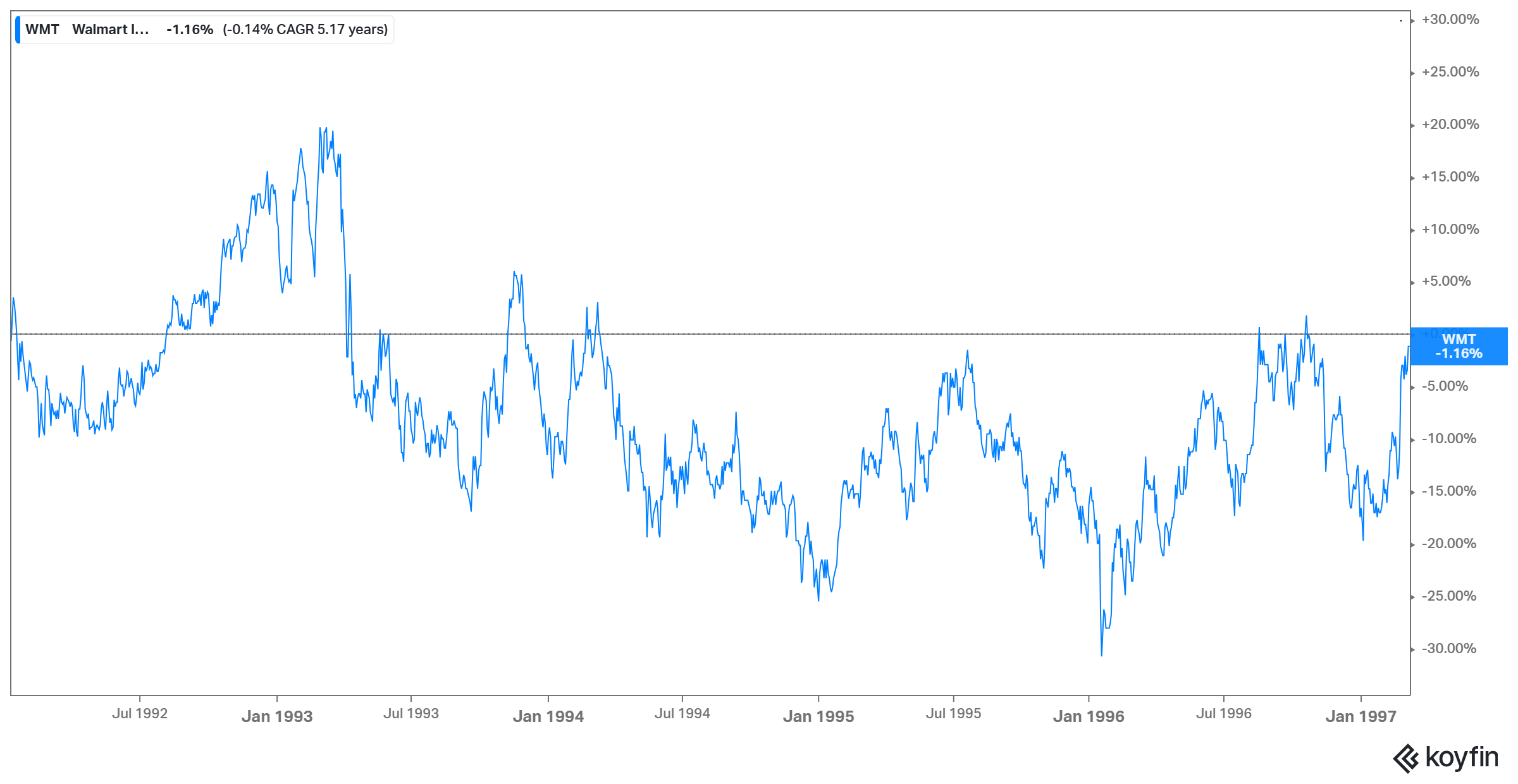

So, what did exactly startle me a bit? Walmart was founded in 1962 and became a public company by 1970. However, it wasn’t until 1988(!) they started selling groceries. Then in just thirteen (!!) years Walmart became the largest grocery player in the US. Imagine getting into a highly competitive, “mature” sector after two and half decades of your operations and then become market leader in that segment in just over a decade!

I went back to Walmart’s 1988 annual report to see what exactly they were talking about their bet on groceries. While we are familiar today with Walmart “Supercenters”, these used to be called “Hypermart” back then. This is what Sam Walton wrote in his annual shareholder letter about this new “experiment”:

Hypermart USA opened it's doors in Garland, Texas, a suburb of Dallas, in December, 1987 and Topeka, Kansas in January, 1988. Hypermart USA may be described as a blend of the best of a Wal-Mart store, a combination supermarket/general merchandise store and a Sam's Wholesale Club. A true experiment, Hypermart USA has received strong initial customer acceptance, but our ability to achieve satisfactory profit objectives is still unknown.

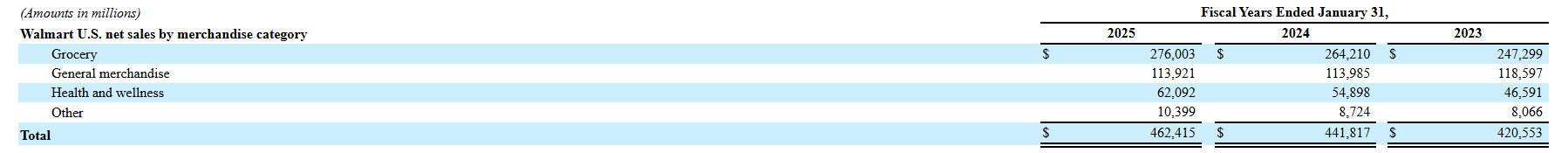

This “experiment” with “unknown” profitability led to $276 Billion sales (~60% of Walmart’s sales in the US) in FY’2025.

Although Sam Walton was still Chairman of the board, interestingly, Walmart’s experiment with groceries coincided with a new CEO: David Glass. It was Glass, who originally joined Walmart in 1976 and took the helm in 1988, aggressively expanded the Supercenter concept. Thankfully, Glass didn’t mind investing “outside a powerful core franchise”. By the time Glass left the CEO role, Walmart was on the verge of becoming the market leader in groceries! So, while Sam Walton still today likely casts his long shadow on Walmart, David Glass deserves plenty of credit and adulation.

Walmart’s success in groceries was the result of a perfect storm of competitive advantages: an entrenched low-price strategy i.e. Every Day Low Prices (EDLP), massive economies of scale, supply chain mastery, a disruptive store format, savvy merchandising (including private brands), and a corporate ethos fixated on cost reduction.

In 1988, none of the traditional grocers had more than ~5–10% of the national grocery market. The industry was still regionally oriented and competitive. Walmart’s competitive advantages deepened over time, and in the 2001 shareholder letter, the new CEO wrote the following:

“This year, Wal-Mart became the largest retailer in the U.S. grocery industry…That is truly a remarkable achievement, and I think Sam Walton would be proud.”

Sam Walton passed away in 1992, but I imagine he would be quite proud indeed!

Meanwhile, the legacy chains consolidated aggressively to defend their positions. Fifteen of the top 20 national grocers in the 1980s either merged or were acquired by the 2000s, reflecting a massive shake-up of the industry. By 2001, Walmart, Kroger, Albertsons, and Safeway stood as the top four grocery seller, with Walmart firmly in the lead.

As you can imagine, Walmart stock did exceedingly well during this period as the stock became ~18x during this 14-year period!

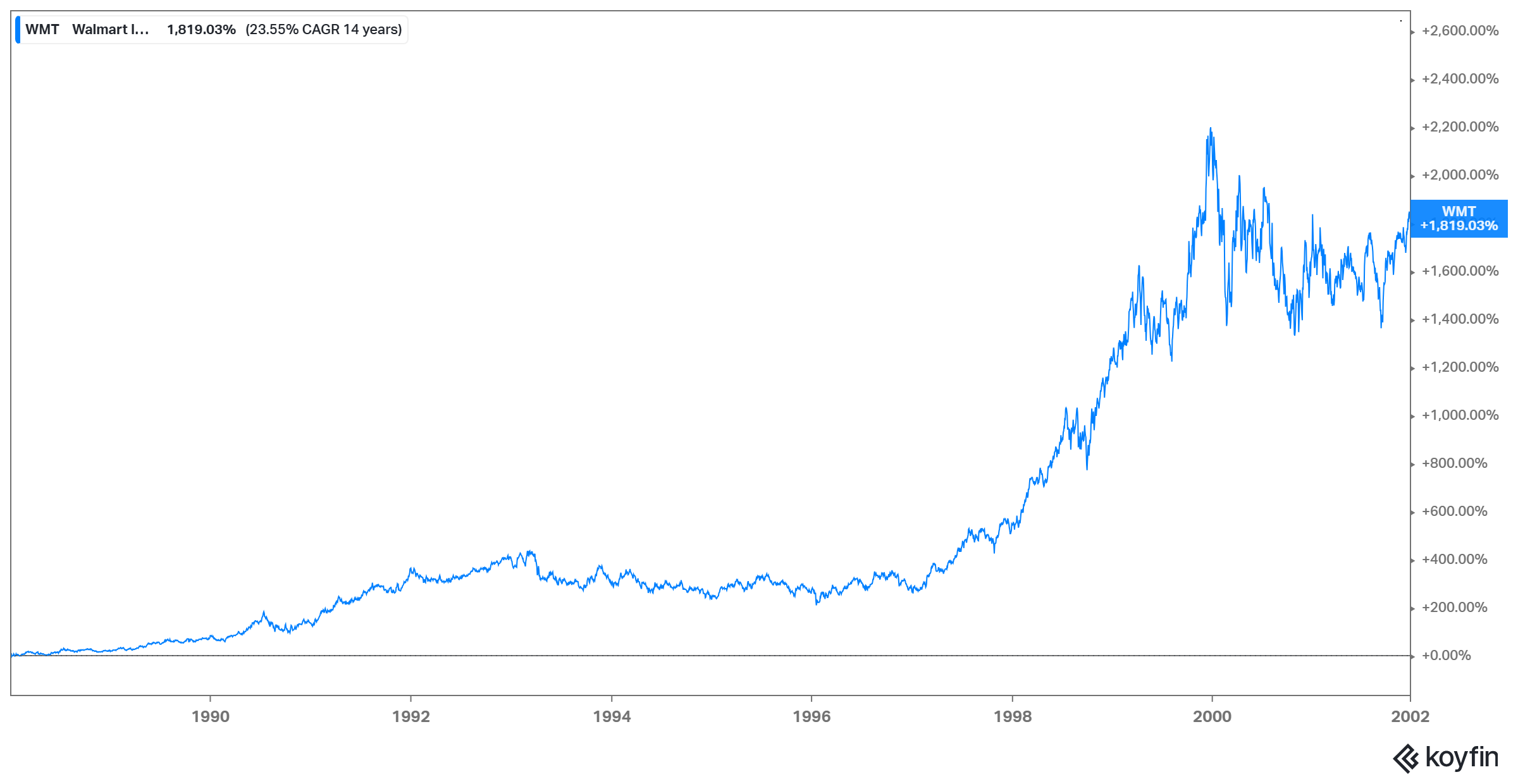

If you look at the chart closely, you will see Walmart stock was dead money from early 1992 to early 1997! I am highlighting this particular period because these periods get often “lost” in a long-term stock charts with gangbuster returns. But take a moment to appreciate the doubts, and criticisms that must have been directed at Walmart’s shareholders back then. Having experienced one such period with Meta Platforms, I can tell these are never fun to go through, but perhaps almost unavoidable for most long-term compounders!

But why was the stock flat for five years despite essentially steamrolling competitor after competitor in grocery market in mid-90s?

Walmart’s net profit actually doubled from $1.6 Billion in FY’92 to $3.1 Billion in FY’97. But growth was decelerating as the base got huge (net-sales growth stepped down from 35% in FY’92 to 12–13% by FY’96–’97). That’s exactly the recipe for de-rating. P/E was basically cut in half.

It also likely didn’t help that mid-90s Walmart spent ~$3–3.5B a year to open/convert stores and build DCs (supercenter roll-out). Operating cash flow couldn’t cover capex (negative FCF) for much of this period, only flipping positive in FY’97. It’s not hard to imagine people complaining about negative FCF year-in-year-out. While those investors must have felt pretty good about their “judgment” to avoid such a capex heavy retailer investing so much in lower margin grocery business, that proved to be a short sighted judgment in hindsight!

None of this means history will repeat for Amazon, but it’s useful historical pre-text before I spend more time understanding Amazon’s bet on groceries. I am not sure how many parts I will write in this series, or when the next parts will come out, but expect me to do more work here in the next few months.

In addition to "Daily Dose" (yes, DAILY) like this, MBI Deep Dives publishes one Deep Dive on a publicly listed company every month. You can find all the 61 Deep Dives here.

Current Portfolio:

Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.

My current portfolio is disclosed below: