Global Payments, Tax Shenanigans

A programming note: I will publish my Deep Dive on Union Pacific (ticker: UNP) tomorrow. Following Union Pacific, the next Deep Dive will be on ASML.

I also wanted to remind you that after switching to a more topical discussion format for the “Never Sell” podcast (see here), I will mostly try to respond to your more open ended questions through the podcast. Since moving to daily publishing schedule, the number of emails I receive per day has increased significantly. It is difficult for me to respond individually, but I encourage you to send questions for the podcast.

Global Payments (GPN)

One of the reasons I am not a big fan of pitching stocks is it can inherently put people in a certain mode of discussing a company. In fact, I have noticed at times that if someone is long a stock, they often only mention risks that they have a decent counter against. And if they’re short, many people seem almost too worried to concede anything positive about the company. Of course, good investors and analysts can spot this and/or are self-aware enough to not fall for this “natural” biases themselves. One investor and analyst who certainly doesn’t fall for this is Scuttleblurb.

Scuttleblurb wrote about Global Payments (GPN) yesterday, a company I have never studied. One of my highlights from the piece was his meticulous track down of all the hodgepodge of acquisitions GPN and other legacy payment acquirers did over the years which was a strong reminder of Adyen’s key strength in competing against these companies. Some excerpts from Scuttleblurb piece:

“…Scarcely in the history of payments have so many bankers been paid such enormous fees for so little value creation.

…From an enterprise value of just ~$3bn in 2012, Global spent $8bn on growthy forward-looking acquisitions, until by 2018 nearly half its revenue came from integrated payments, e-/omnichannel commerce, and vertical software, business lines that hadn’t existed prior to this transformative journey. In the heady days of the late-2010s, with the market gushing over software, management encouraged analysts to value the company on a sum-of-the-parts basis.

…I mean, just an absolutely bewildering frenzy of acquisitions that go so many layers deep and encompass so many different processing engines across so many geographies that it comes as no surprise whatsoever that all attempts to consolidate them have utterly failed and long been abandoned. First Data tried for close to a decade before giving up. Vantiv eventually dropped the phrase “single platform” from its 10K. Adyen scanned at the mosh pit and rightly determined that the only way forward was to “start over again”.

…The only time investors in legacy acquirers ever seem to hear the ugly God’s honest truth about how things are going is when it comes out of the mouth of a new CEO, when the incentive to come clean and heap blame on the prior regime are at their peak.

…Legacy acquirers are masters at financial engineering but amateurs at organic development and execution. Their hungry eyes are sensitized to the nickels of cost synergies laying right before them and blind to the dollars that could be captured further down the road by tuning in to marketplace realities and adapting accordingly.

…Legacy players chant “scale” like a hallowed incantation, as if size were the end all, regardless of how many regional platforms it was distributed across. And I’ll concede that decades ago legacy acquirers could get away with trumpeting cost synergies, neglecting product development, and forsaking the hard work of integrating acquired platforms. All sucked at innovation and platform integration together; all enjoyed close relationships with the banks and ISOs that controlled distribution. But that doesn’t cut it anymore. Stripe abstracted its payments apparatus behind a simple API that was rapidly adopted by developers; Adyen sold directly to e-commerce enterprises; Square terminals could be picked off the shelves of major retailers or ordered online. All prioritized easy onboarding and beautiful design, and eschewed the legacy model of scaling through transformative M&A, understanding that the easy wins (immediate scale, cost synergies) from such an approach could morph into an addiction that eventually concretizes into a millstone around the necks of those who succumb to it. In short, you can’t buy your way to relevance anymore.

After reading all that, it may be surprising to some that he actually is long the stock:

As you’ve no doubt gathered, I dislike the Worldpay acquisition. Global shareholders would be much better served by the focused agenda that management had in place prior to this year. But here we are! And God help me, for all the knocks against the company, the stock looks pretty damn cheap. On a standalone basis, Global trades at less 7x this year’s net earnings. The Worldpay transaction is expected to be accretive on day 1, so the stock is even cheaper than that on a pro-forma basis, even without taking into account the $600mn of cost synergies (18% of WP’s cost base). At the current price, an investor need not believe that Global will crash payments Olympus and claim a seat alongside Adyen and Stripe. Just that it won’t be snuffed out of existence. Humbly, I don’t think this is too difficult a bet to underwrite.

I have always learned a lot about payments by studying Scuttleblurb’s work. I always appreciate the nuances embedded in his pieces instead of a narrow lens of a particular long/short view. While many readers perhaps would rather read stock pitches over research pieces rambling around to sometimes nowhere, building foundational knowledge over time is critical for survival of any active investor.

Tax Shenanigans

Brad Setser wrote quite a revealing piece on how pharmaceutical companies have used tax shenanigans to avoid paying taxes in the US:

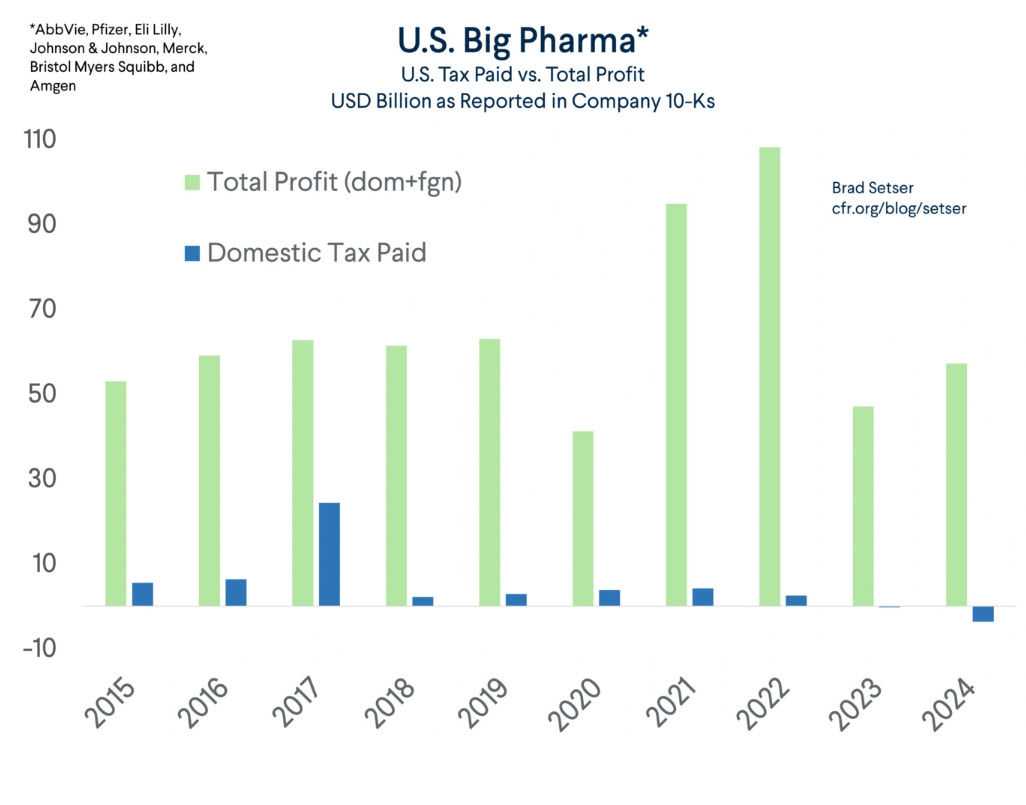

“…America’s top pharmaceutical firms have basically stopped paying corporate income tax in the U.S.

…The top seven pharmaceutical companies are paying $10 billion or so in tax on their $70 billion in offshore profit. They are just paying all that tax abroad.

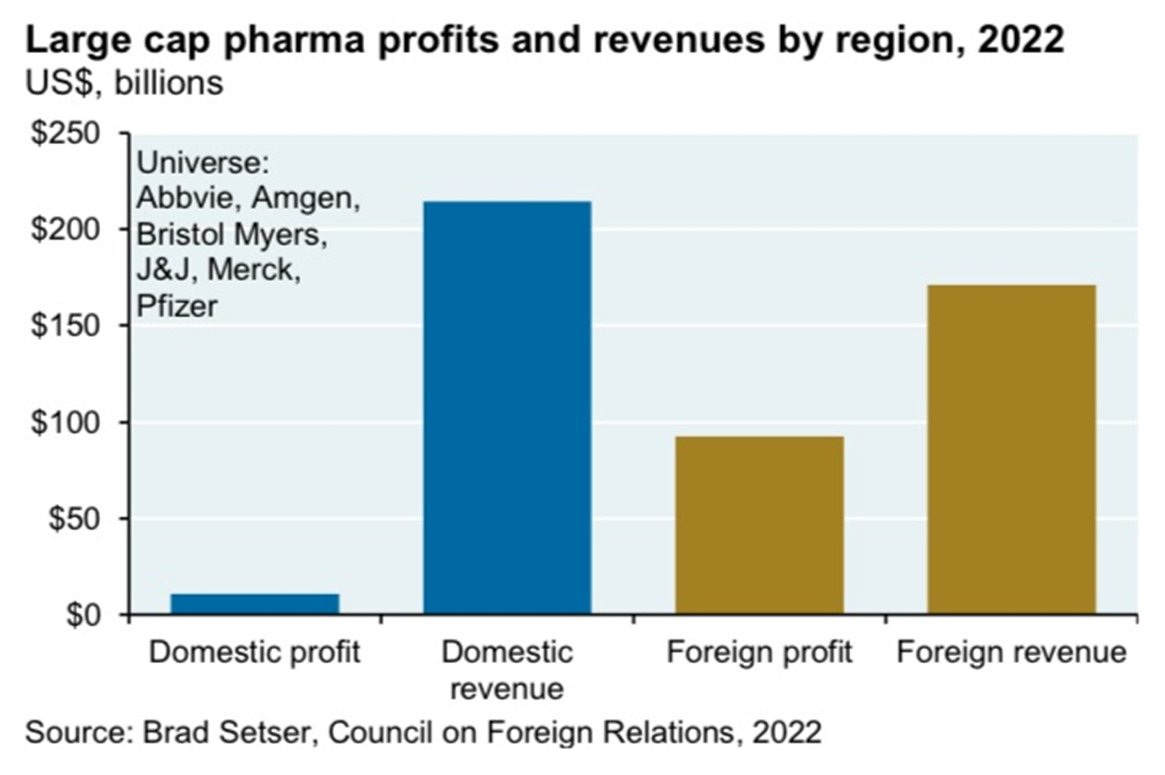

This looks really, really bad when you juxtapose US revenue vs reported profit in the US.

How do these companies do it? From Brad Setser:

Conduct a few transactions to move the right to profit from the firms’ intellectual property to an offshore subsidiary in a low-tax jurisdiction, produce those drugs abroad, and import them to the U.S. (the pre-Trump pharmaceutical tariff was zero) and pay the 10.5 percent global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) rate rather than the 21 percent headline tax rate on profits derived largely from U.S. sales.

Of course, pharmaceutical companies are not the only companies doing these shenanigans. Again, from Brad Setser:

Apple reported $80 billion ($78.3 billion) in offshore profit in 2024, up from around $70 billion in 2023. Microsoft reported $45 billion in offshore profit in 2024, and $36 billion in 2023.

That is just under $200 billion in offshore profits from fewer than ten companies, and a large share of the $350 billion that the U.S. balance of payments data shows that American firms earned in low tax jurisdictions in 2023.

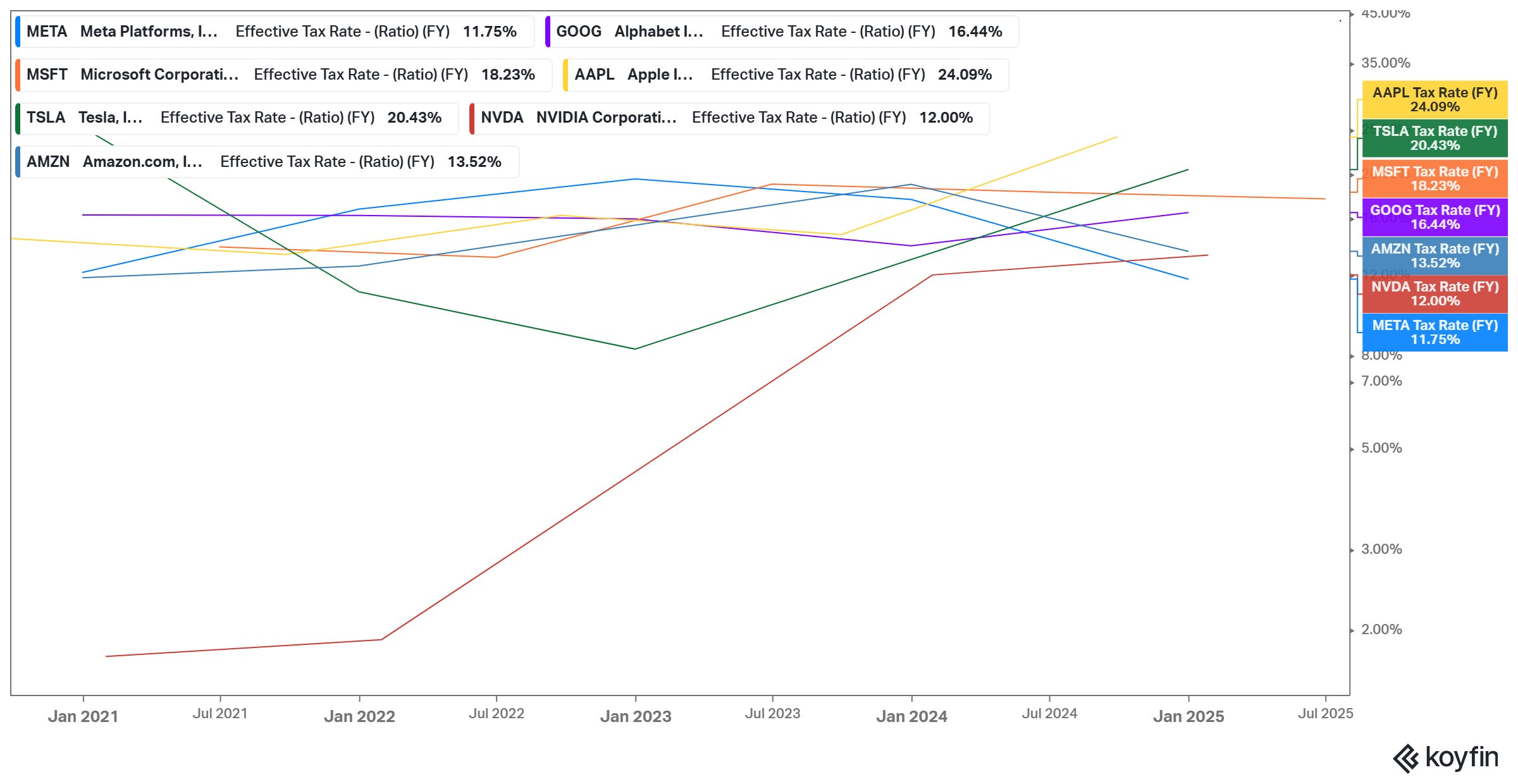

I own some of these big tech companies, and I have always disliked these tax shenanigans as I believe given the size of these big tech companies and how the rest of the world will increasingly look to milk these companies through random regulations, they need US government to be on their side to vociferously make their case. US government would be lot less willing (or worse, they could try to milk them as well) if these companies don’t actually pay much taxes here. Paying lower taxes can lift short-term EPS for these big tech companies but can really hurt their long-term earnings power if governments around the world start thinking they’re easy target. I have always felt a little uneasy whenever I see effective taxes for all the big tech are consistently noticeably below the statutory rate. In fact, when I model these companies, I always assume the statutory tax rates going forward as I do believe that’s indeed the long-term equilibrium for these companies.

It can be instructive to notice when big tech are trying to pay less taxes in the US, Warren Buffett is trying to ensure everyone knows how much taxes Berkshire is paying. From Buffett’s 2024 shareholder letter:

“…Berkshire Hathaway – paid far more in corporate income tax than the U.S. government had ever received from any company – even the American tech titans that commanded market values in the trillions.

To be precise, Berkshire last year made four payments to the IRS that totaled $26.8 billion. That’s about 5% of what all of corporate America paid.

As these companies become larger and larger over time, their roles will be increasingly scrutinized in every society. The value proposition they bring not just through economic and consumer surplus but their direct contribution to government coffers can be an important tool to have the most powerful government in the world to be on their side. I hope and expect the big tech companies, especially the founder led ones optimize their future for the very long term.

In addition to "Daily Dose" (yes, DAILY) like this, MBI Deep Dives publishes one Deep Dive on a publicly listed company every month. You can find all the 61 Deep Dives here.

Current Portfolio:

Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.

My current portfolio is disclosed below: