Instacart: "Webvan done right"

You can listen to this Deep Dive here

With a 10-month old son, MBI household understandably doesn’t quite enjoy going to grocery stores. So our habit of ordering grocery online survived longer than perhaps many families did since the pandemic. Since every member of MBI household, including my son, owns Amazon shares, I cajoled my wife to use Amazon for ordering grocery as well. To my persistent annoyance, I keep finding my wife ordering grocery via Instacart. But that’s how I also knew I should study Instacart closely.

Instacart was founded by Apoorva Mehta in 2012. Born in India but raised in Canada, he studied engineering at the University of Waterloo, and then actually went to Amazon to work on supply‑chain systems. In his early 20s, he then had the brilliant idea of starting a company…any company! Mehta didn’t have any particular “calling”; from an ad network for social games, a Groupon‑for‑food variant, even a social network for lawyers, he tried many things but thankfully, he failed fast. So, he didn’t toil in obscurity to pursue these ideas for too long.

Then the story goes, the spark for Instacart came from a near‑empty fridge when he was living in San Francisco and a feeling that everything except groceries had already moved online. Mehta wanted a low‑friction way to buy basics without dedicating hours to aisles and checkout lines. The thesis was simple: groceries are enormous, habitual, and still offline; smartphones could turn that habit into an app.

He wrote the first version of the app in three weeks and stress‑tested it the only way a one‑person startup can: by ordering from himself. He placed an order, drove to the store, shopped, delivered, and of course, tipped himself. That small loop proved the mechanics worked: if the app could connect a buyer to a nearby human with a car, there is no compelling reason why groceries cannot be ordered online and then get delivered to people’s homes.

Of course, this simple idea didn’t just occur to Mehta first. Webvan tried the idea of online grocery delivery and spectacularly failed by filing for bankruptcy in just five years after the company was founded. Mehta recalled how one of his meetings with a VC went:

I remember there was an investor meeting that I had in the early days and I walk into this meeting and I start presenting. And this is like 24-year-old Apoorva. I wanted to really stand out. The title under my logo was Webvan done right. And I started, got to the second slide, third slide, and this investor literally got up and left the room and I was like, Is the meeting over? It’s very clear I didn’t get the term sheet. But then he came back and he slapped this floppy disk on the desk on the table. And he was like, this has the Webvan business plan, you should go home and study it and you will never do this company.

This story reminded me of Corry Wang’s tweet:

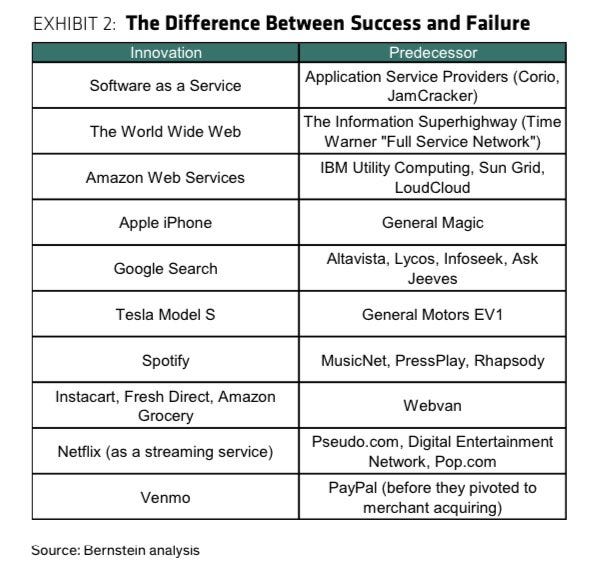

I always joke that predicting the future is easy - most good ideas are “obviously” good ideas. And over a long enough time horizon, almost every good idea will work eventually. The hard part is figuring out whether this time is different

Indeed, grocery delivery is one of those “obviously good ideas” and fortunately for Instacart, the timing was right! While smartphones were certainly a godsend for Instacart’s adoption, it was far from a panacea. The idea was still ahead of its time as the overall grocery value chain was lagging behind in its tech adoption. From Apoorva Mehta:

…what we did was we invented this thing called ninja shopping, which was effectively that we would just go to a store, buy the stuff off the shelf, go to the checkout, and deliver the groceries to the customers. And the only problem was we didn’t know what any of the stores actually carried…and you couldn’t find it anywhere online. I was totally okay scraping stuff, but you just couldn’t find it. And some of these SKUs didn’t even have any online information about them at all.

So what we decided to do was we went to many different stores and picked up one of every single thing from the store, took it to a studio, photographed everything, and then uploaded all that onto Instacart. And it cost us like $50,000 to do that, to buy the entire grocery store. But that allowed us to bootstrap our supply. And so now it immediately became something that customers wanted. And I remember we did this for one of the stores, and overnight our demand doubled.

Mehta ended up meeting his co-founders: Max Mullen and Brandon Leonardo at YC, and they all focused on how to avoid Webvan’s fate. Instacart’s operating principle was simple and strikingly different from Webvan: use existing grocers as decentralized “warehouses,” crowdsource shoppers and delivery, and focus on dispatch, routing, batching, and reliability. That asset‑light stance was in stark contrast to capital‑heavy parallel supply chains. The decision let Instacart launch quickly and iterate where it held leverage: software and marketplace liquidity.

Instacart expanded beyond San Francisco, wiring inventory from partners into the app and leaning on flexible shoppers to hit one to two‑hour delivery windows. The company’s bet of layering software atop retailers instead of replacing them saved millions in startup costs and let it spread faster than warehouse‑based rivals. However, Instacart still faced some near death experience; one such experience was when Amazon acquired Whole Foods in 2017! Mehta explained how that particular saga turned out to be actually positive for Instacart:

I got a call from the Whole Foods CEO at 6:00 AM in the morning. All right, at this time, Whole Foods was the largest partner of ours. They had about, I think 30% to 40% of our overall sales were coming from Whole Foods. And so of course, I was going to take the call. It didn’t matter if it was 06:00 AM. And I get on a call with him. He tells me that Amazon had just paid like $18 billion to buy Whole Foods.

Now, I’m a very paranoid person, and you tend to be that when you’re a founder, you have to understand where risks are in your business. But this was not in my risk bingo card and was a very short call because I didn’t know what to say to him. And I was just refreshing my social feed. And as soon as that announcement happened, the next set of announcements were, oh, Instacart’s dead. And we started getting text messages from investors and parents asking us if we’re okay. And it kind of felt like this was going to be it. Like this was going to be my 21st failure of a company because now our largest competitor owned our largest partner.

And so at the time I called in all hands, told the team that we were in war mode and the only thing that mattered at this point was to fight this battle. In the next couple of weeks, we came together with a plan, and this was a high beta plan, very high-risk plan, which was that we were going to sign every major grocery retailer onto our platform and we were going to rapidly increase the Instacart membership so that we would be able to retain most of these customers. And me and the team, we were on the phone with effectively every retail CEO in America talking about what we could do.

We had this concept of the alliance of the willing. We were calling it internally, but really it was how do we figure out how do we work with retailers? And we looked at every single thing that we could do to get them over the line, which was how do we rapidly expand nationwide? So that we were everywhere. We were in Rockford, Illinois. We were in Lubbock, Texas. In the smallest cities, Instacart worked. And we figured out how to make the economics work in the smallest cities because that’s what it would take for some of these larger retailers to sign with us. We scaled Instacart enterprise with all kinds of functionality that would make it so that these retailers felt comfortable putting their brand onto Instacart. And there was no meeting that we would not do in person. Regardless of how many red eyes we had to take, we made it happen.

And by the time Whole Foods finally left the Instacart platform, they were less than 5% of our sales. We had continued to drive a lot of growth and we had virtually every major grocery retailer on our platform. And so at the time, of course, this felt like we’re not going to make it, but actually ended up being one of the best things that could have happened to the company.

Instacart survived and then thrived even after departure of Whole Foods from Instacart app. Then of course, the pandemic happened which was basically manna from heaven for Instacart. The company then raised a whopping $265 million at an eyepopping valuation of $39 Billion in April 2021. That has proved to be the absolute peak for Instacart’s valuation…at least for quite some time.

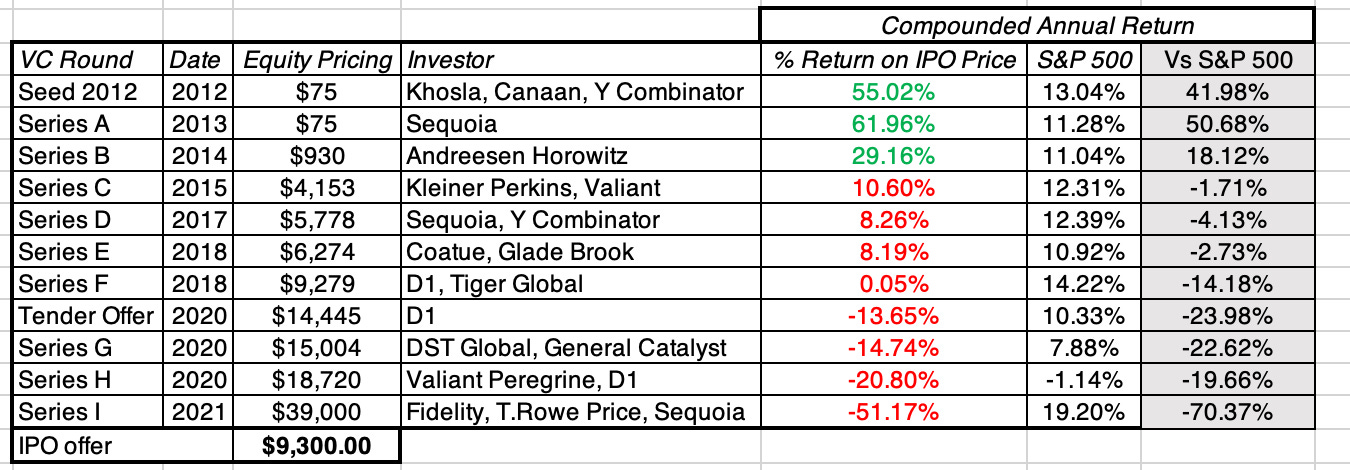

Just a couple of months after the capital raise, Mehta left the CEO role back in August 2021 and handed the leadership baton to Fidji Simo who used to lead the Facebook app. Given ads are of paramount importance for profitability, Simo’s pedigree perhaps outweighed any concerns that would naturally arise from a founder’s exit. Instacart finally came to IPO at just ~$9 Billion valuation in 2023, almost ~70% below its peak valuation in 2021. Aswath Damodaran shared the below table back then which made it clear even an IPO exit may mean a very shabby return for a lot of VCs!

Despite coming to IPO at ~70% below its peak valuation, Instacart stock lagged both S&P 500 and QQQ considerably. Instacart’s valuation has been almost flat since 2018! To put this in context, Instacart’s revenue increased by ~16x between 2019 and 2024 and yet its shareholders didn’t make much money during this period. It may be helpful to remember no matter how “clear” the story seems in the short-term, the weight of long-term fundamentals may come for all.

So where does Instacart go from here? Before we ponder about that question, let’s have a deeper understanding of their business today.

Then I will assess the competitive dynamics they are facing as well as Instacart’s capital allocation philosophy and management incentives. Finally, I will show what assumptions are embedded in current stock price. The rest of the Deep Dive is behind the paywall.

MBI Deep Dives publishes one Deep Dive on a publicly listed company every month. You can find all the 64 Deep Dives here. Subscribers also receive one email everyday on topics/companies I am interested in.