MBI Daily Dose (July 19, 2025)

Companies or topics mentioned in today's Daily Dose: OpenAI Agent, Elephant Graph

OpenAI launched “OpenAI Agent” last week. It’s basically a marriage between “Deep Research” and “Operator”, but what’s new is the orchestration layer on top i.e. an agentic planner that decides when to invoke which skill, manages short‑term working memory, and runs multi‑step workflows inside the familiar chat interface, rather than two separate tools.

I still haven’t got access to it, so I haven’t played with it yet. But I was quite impressed with the tool when I saw it in action here which asked the agent to perform a redesign of Wikipedia in the styles of Airbnb and OpenAI websites (I came across this example via “Enterprise AI Trends” Substack). The agent worked on it for 50+ minutes; I suggest you click the link to watch it work on this problem (just watch for a couple of minutes).

So, here’s the prompt: I want two variations of a redesign of wikipedia.com in the style of 1) OpenAI's home page, as well as 2) Airbnb's home page. When doing the redesign, use the same aesthetics and design system (typography, spacing, etc) that you can infer from the respective home pages. Just the home page itself will be fine.

Let me show you the final output of the redesign in OpenAI style. It’s pretty damn impressive!

I recently read this paper which probes into the winners and losers of globalization during 1988 to 2008 period. Most of it lines up with my intuition, but still quite interesting to see the numbers. Some excerpts from the paper (emphasis mine):

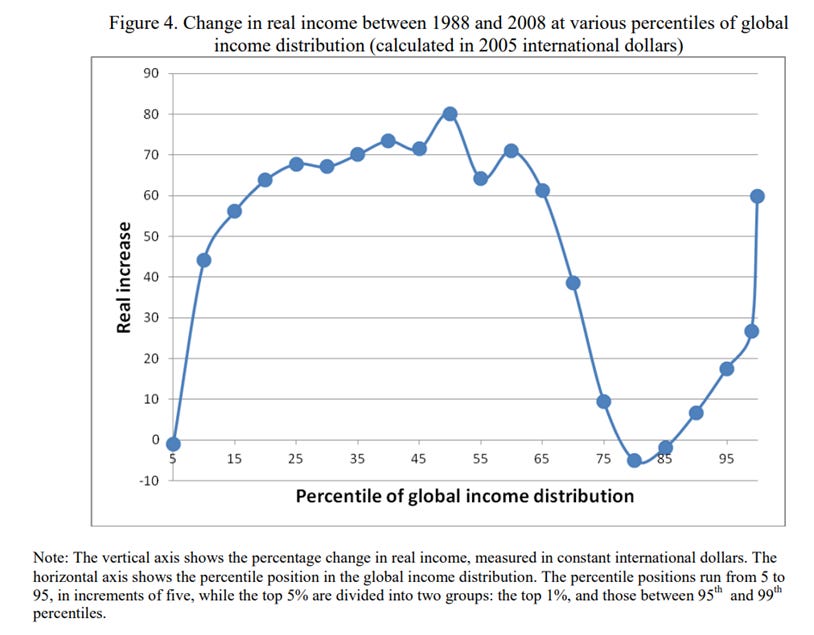

What parts of the global income distribution registered the largest gains between 1988 and 2008? As the figure shows, it is indeed among the very top of the global income distribution and among the “emerging global middle class”, which includes more than a third of world population, that we find most significant increases in per capita income. The top 1% has seen its real income rise by more than 60% over those two decades. The largest increases however were registered around the median: 80% real increase at the median itself and some 70% around it. It is there, between the 50th and 60th percentile of the global income distribution that we find some 200 million Chinese, 90 million Indians, and about 30 million people each from Indonesia, Brazil and Egypt. These two groups—the global top 1% and the middle classes of the emerging market economies— are indeed the main winners of globalization.

The surprise is that those at the bottom third of the global income distribution have also made significant gains, with real incomes rising between more than 40% and almost 70%. The only exception is the poorest 5% of the population whose real incomes have remained the same. It is this income increase at the bottom of the global pyramid that has allowed the proportion of what the World Bank calls the absolute poor (people whose per capita income is less than 1.25 PPP dollars per day) to go down from 44% to 23% over approximately the same 20 years.

But the biggest losers (other than the very poorest 5%), or at least the “non-winners,” of globalization were those between the 75th and 90th percentiles of the global income distribution whose real income gains were essentially nil. These people, who may be called a global upper middle class, include many from former Communist countries and Latin America, as well as those citizens of rich countries whose incomes stagnated.

Global income distribution has thus changed in a remarkable way. It was probably the profoundest global reshuffle of people’s economic positions since the Industrial revolution. Broadly speaking, the bottom third, with the exception of the very poorest, became significantly better-off, and many of the people there escaped absolute poverty. The middle third or more became much richer, seeing their real incomes rise by approximately 3% per capita annually.

The most interesting developments, though, happened among the top quartile: the top 1%, and somewhat less so the top 5%, gained significantly, while the next 20% either gained very little or faced stagnant real incomes. This created polarization among the richest quartile of world population, allowing the top 1% to pull ahead of the other rich and to reaffirm in fact -- and even more so in public perception -- its preponderant role as winners of globalization.

Who are the people in the global top 1%? Despite its name, it is a less “exclusive” club than the US top 1 percent: the global top 1% consists of more than 60 million people, the US top 1% of only 3 million. Thus, among the global top percent, we find the richest 12 percent of Americans (more than 30 million people) and between 3 and 6 percent of the richest Britons, Japanese, Germans, and French. It is a “club” still overwhelmingly composed of the “old rich” world of western Europe, northern America and Japan. The richest 1% of the embattled Euro countries of Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece are all part of the global top 1 percentile. However, the richest 1% of Brazilians, Russians and South Africans belong there, too.

To which countries and income groups do the winners and losers belong? Consider the people in the median of their national income distributions in 1988 and 2008. In 1988, a person with a median income in China was richer than only 10% of world population. Twenty years later, a person at that same position within Chinese income distribution, was richer than more than one-half of world population. Thus, he or she leapfrogged over more than 40% of people in the world.

So who lost between 1988 and 2008? Mostly people in Africa, some in Latin America and post-Communist countries.”

In addition to "Daily Dose" like this, MBI Deep Dives publishes one Deep Dive on a publicly listed company every month. You can find all the 60 Deep Dives here.

Prices for new subscribers will increase to $30/month or $250/year from August 01, 2025. Anyone who joins on or before July 31, 2025 will keep today’s pricing of $20/month or $200/year.

Current Portfolio:

Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.