The Slow Singularity

I often come across almost a steady stream of tweets from people mostly in tech (and sometimes in finance) that imply you have a very short period of time left to “escape the permanent underclass”. These tweets have a tinge of humor and warning associated with such an outlook of the future.

So, how do you escape such “permanent underclass”? These tweets allude that you must amass a lot of capital and use that capital to buy equities into companies that will lead the age of machines to automate almost everything in sight. Stanford Professor Charles Jones and Christopher Tonetti’s recent working paper titled, “Past Automation and Future A.I.: How Weak Links Tame the Growth Explosion” may pour some cold water on such simplistic framework of the future. Their research suggests that while AI will indeed drive accelerating growth, the transition may be far slower than the hype suggests.

To understand why the future might be sluggish, the authors first had to decode the past. In a methodological twist that fits the subject matter perfectly, they employed OpenAI’s Deep Research to dig through economic history and construct a dataset of 150 essential tasks over the last century. This analysis revealed a counterintuitive "Zero Productivity Paradox" as switching a task from labor to capital contributes zero to Total Factor Productivity (TFP) growth at the exact moment it happens. This is because firms switch exactly when the costs are equal. The growth comes entirely from what happens after the switch: the task is now performed by a machine that improves exponentially faster than a human.

They estimate that while machine productivity on automated tasks grows at a blistering 5% annually, human task efficiency grows at a meager 0.5% and in some sectors, human efficiency appears to be declining. To prove how vital this dynamic is, they calculated a "frozen" counterfactual: if we had stopped automating new tasks in 1950, but allowed computers to keep getting faster at the things they were already doing, US economic growth would have essentially flatlined for the last 70 years. We may be accustomed to growth given our own life experiences, but it is a good reminder that our life experiences are in stark anomaly to much of the history of human civilization which largely operated in stagnation for centuries. Without constantly pushing the technology frontier, growth may again become elusive. Growth basically requires a constant widening of the automated circle, and not just better machines inside the existing circle.

The paper mentioned the economic irony we all intuitively know: abundance often leads to a loss of value. The following excerpts from the paper was particularly eye-opening:

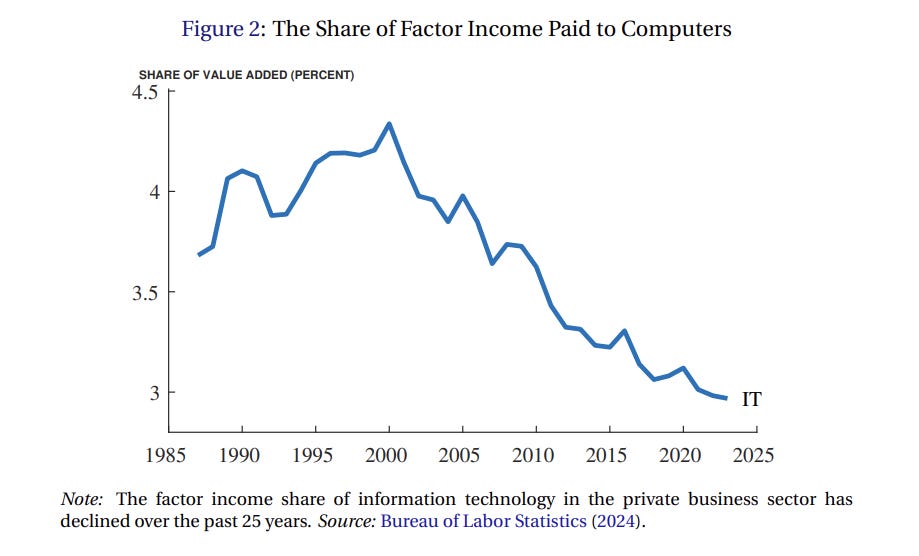

…it is useful to consider the following question: We know that the share of factor income paid to capital has risen in recent years. What has happened to the share of factor income paid to computers? On the one hand, computers are everywhere. The number of transistors on a computer chip today is 50 million times more than it was in the 1970s. On the other hand, the price of compute has plummeted, suggesting that the marginal product of computing power has as well. Which effect dominates?

During the dot-com era of the late 1990s, the factor share of income for computers rose from around 3.7 percent to 4.3 percent. But since 2000, the share has fallen substantially to 3.0 percent. In other words, even though the amount of computing power has exploded, we pay less of our GDP as a return to computers today than in the past. This is exactly what a production function with an elasticity of substitution less than one would predict. And this fact may itself be very informative about the effects of future A.I.-driven automation on the economy.

The same logic explains why the AI “singularity” is likely to be a slow burn rather than an explosion. The economy operates on a “weak link” principle. Production requires a chain of complementary tasks; you need high-speed coding, but you also need management, legal compliance, physical logistics etc. Because these tasks are interlinked, the economy is constrained by its slowest components. Even if AI automates cognitive tasks with infinite speed, total output remains bottlenecked by the essential tasks that still require slow-improving human labor. The math is quite sobering here even if you assume a fantastical automation future in cognitive tasks. From the paper (please note that sigma represents the elasticity of substitution between the different tasks required to produce the final output):

Given the advances in LLMs at coding, software is generally thought to the one of the first industries that will be largely automated by A.I. The share of software in GDP is around 2%. This means that automating all the tasks that are currently done by software with infinite productivity would only raise GDP by about 2% when σ = 1/2

More speculatively, transformative A.I. is thought to move on to automating all cognitive tasks — anything that could be done by a remote worker with a computer could potentially be done by an A.I. agent. Around two thirds of GDP is paid to labor. We consider what would happen if half of this were fully automated with infinite productivity. With σ = 1/2…gives a gain of…1.5; that is, infinitely automating 1/3 of GDP would only raise GDP by 50%. At some level, this number seems quite small; after all we have infinite productivity on a third of current GDP. However, the logic is again one of weak links. The economy is constrained by the other two-thirds of tasks that are not automated. But an alternative way to view the 50% gain is that if it were to occur over a decade, this would correspond to an increase in GDP growth of around 5% per year; over two decades it would correspond to more than 2pp of extra annual growth.”

As long as there are essential tasks that only humans can do, our own limitations will act as a governor on the engine of growth. The singularity may be coming, but it may have to arrive at a human pace.

In addition to “Daily Dose” (yes, DAILY) like this, MBI Deep Dives publishes one Deep Dive on a publicly listed company every month. You can find all the 65 Deep Dives here

Current Portfolio:

Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.

My current portfolio is disclosed below: