"The Compute Theory of Everything"

One of my favorite recent genre of content these days is annual reflection from AI researchers. Dan Wang isn’t an AI researcher, but I think his fantastic annual letters was inspiration among many. I will admit that through his letters, Wang has singlehandedly elicited from me a sense of affection and admiration for China and its people. In fact, his writings at least partly influenced me on how I would like the AI race between China and the US to be settled. As someone living in the US and heavily invested in the US companies, I certainly have my biases towards the US, but nowadays I basically don’t want the race to be settled overwhelmingly in the US’s favor. I would like a genuine uncertainty about the outcome of this race for hopefully forever. If there is no such genuine uncertainty, I suspect policies such as moratorium on data centers in the US (and perhaps the entire Western hemisphere) may gain a decisive popularity over time. I also wonder whether each of these super powers may behave a lot better with the rest of the world if either of them does not have a decisive and sustained advantage over the other.

Anyways, I do think essays are generally deeply underrated, and I wish more bright people penned how they’re perceiving the world through their lens. Some of the annual letters/reviews/reflections that caught my attention this year are by Andrej Karpathy, Zhengdong Wang, and Samuel Albanie. It was Albanie who coined “the compute theory of everything” in his letter. Albanie referred two seminal essays by Hans Moravec: “The Role of Raw Power in Intelligence” (1976), and “When will computer hardware match the human brain?” (1998)

I glanced through the first essay, but read the second one. I was moved just by reading the abstract of the paper:

“This paper describes how the performance of AI machines tends to improve at the same pace that AI researchers get access to faster hardware. The processing power and memory capacity necessary to match general intellectual performance of the human brain are estimated. Based on extrapolation of past trends and on examination of technologies under development, it is predicted that the required hardware will be available in cheap machines in the 2020s.”

Moravec is a familiar name to me because I have heard about Moravec’s paradox before, but it was in this 1998 essay he provided a metaphor for AI progress that defied the intuition that reasoning is hard and “sensing” is easy. He described human skills as a landscape where AI is a rising flood. From the paper (all emphasis mine):

“Computers are universal machines, their potential extends uniformly over a boundless expanse of tasks. Human potentials, on the other hand, are strong in areas long important for survival, but weak in things far removed. Imagine a "landscape of human competence," having lowlands with labels like "arithmetic" and "rote memorization", foothills like "theorem proving" and "chess playing," and high mountain peaks labeled "locomotion," "hand−eye coordination" and "social interaction." We all live in the solid mountaintops, but it takes great effort to reach the rest of the terrain, and only a few of us work each patch.

Advancing computer performance is like water slowly flooding the landscape. A half century ago it began to drown the lowlands, driving out human calculators and record clerks, but leaving most of us dry. Now the flood has reached the foothills, and our outposts there are contemplating retreat. We feel safe on our peaks, but, at the present rate, those too will be submerged within another half century. I propose that we build Arks as that day nears, and adopt a seafaring life!”

Indeed, AI conquered chess (foothills) decades before it could reliably fold laundry or navigate a cluttered room (the peaks), which remain difficult engineering challenges today. Hence, the Moravec’s paradox.

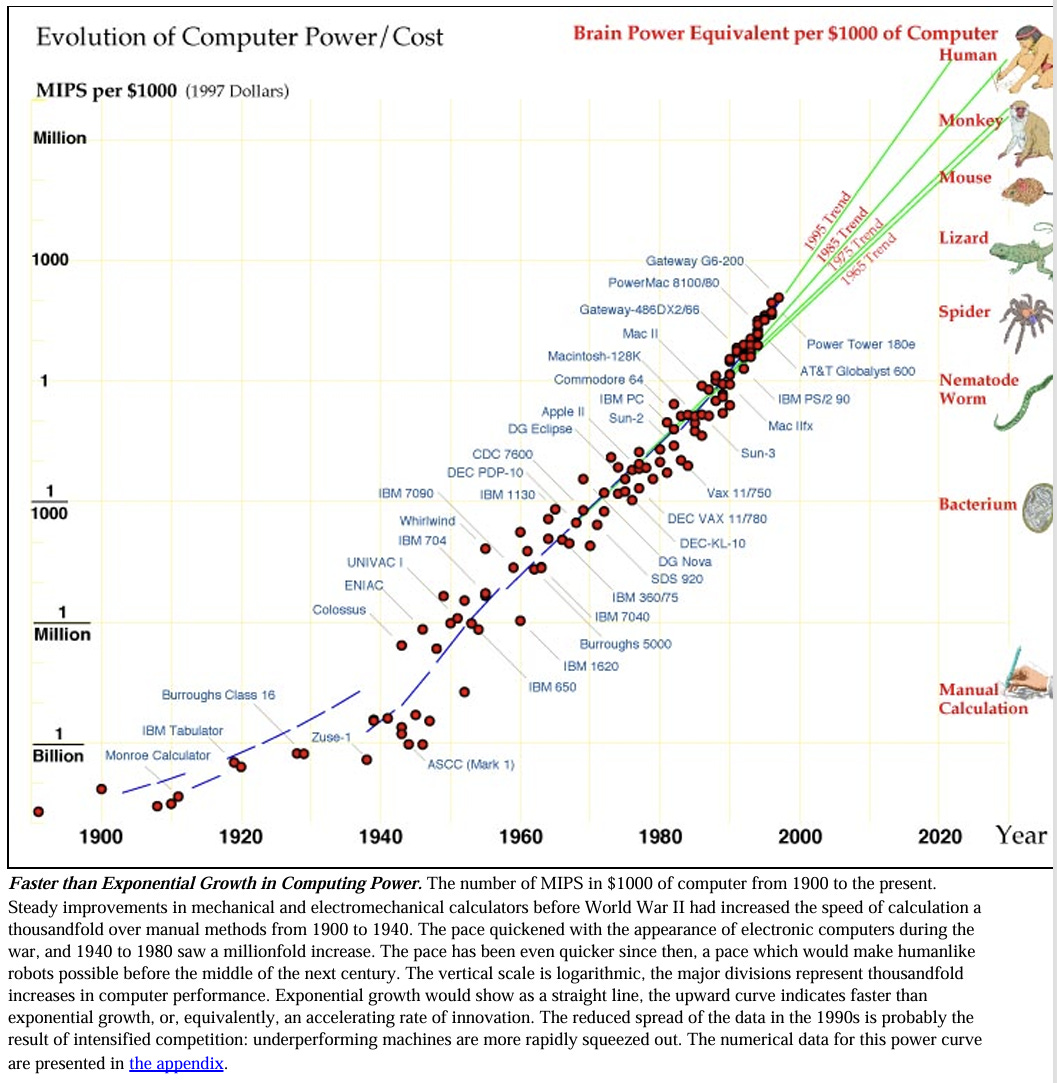

As I have mentioned before, Moore’s law had plenty of skeptics along the way. Moravec was no such skeptic. Despite acknowledging valid reasons to harbor skepticism, Moravec relied on his simple observations on computing:

“Computers doubled in capacity every two years after the war, a pace that became an industry given: companies that wished to grow sought to exceed it, companies that failed to keep up lost business. In the 1980s the doubling time contracted to 18 months, and computer performance in the late 1990s seems to be doubling every 12 months

At the present rate, computers suitable for humanlike robots will appear in the 2020s. Can the pace be sustained for another three decades? The graph shows no sign of abatement. If anything, it hints that further contractions in time scale are in store. But, one often encounters thoughtful articles by knowledgeable people in the semiconductor industry giving detailed reasons why the decades of phenomenal growth must soon come to an end.”

What perhaps moved me the most from Moravec’s 1998 paper was his lucid explanation why AI suffered a long winter. Moravec offered a fascinating economic explanation for why AI stalled between 1960 and 1990. From his paper (note: MIPS stands for Millions of Instructions Per Second):

“In the 1950s, the pioneers of AI viewed computers as locomotives of thought, which might outperform humans in higher mental work as prodigiously as they outperformed them in arithmetic, if they were harnessed to the right programs. Success in the endeavor would bring enormous benefits to national defense, commerce and government. The promise warranted significant public and private investment. For instance, there was a large project to develop machines to automatically translate scientific and other literature from Russian to English. There were only a few AI centers, but those had the largest computers of the day, comparable in cost to today's supercomputers. A common one was the IBM 704, which provided a good fraction of a MIPS.

By 1960 the unspectacular performance of the first reasoning and translation programs had taken the bloom off the rose, but the unexpected launching by the Soviet Union of Sputnik, the first satellite in 1957, had substituted a paranoia. Artificial Intelligence may not have delivered on its first promise, but what if it were to suddenly succeed after all? To avoid another nasty technological surprise from the enemy, it behooved the US to support the work, moderately, just in case. Moderation paid for medium scale machines costing a few million dollars, no longer supercomputers. In the 1960s that price provided a good fraction of a MIPS in thrifty machines like Digital Equipment Corp's innovative PDP−1 and PDP−6.

The field looked even less promising by 1970, and support for military−related research declined sharply with the end of the Vietnam war. Artificial Intelligence research was forced to tighten its belt and beg for unaccustomed small grants and contracts from science agencies and industry. The major research centers survived, but became a little shabby as they made do with aging equipment. For almost the entire decade AI research was done with PDP−10 computers, that provided just under 1 MIPS. Because it had contributed to the design, the Stanford AI Lab received a 1.5 MIPS KL−10 in the late 1970s from Digital, as a gift.

Funding improved somewhat in the early 1980s, but the number of research groups had grown, and the amount available for computers was modest. Many groups purchased Digital's new Vax computers, costing $100,000 and providing 1 MIPS. By mid−decade, personal computer workstations had appeared. Individual researchers reveled in the luxury of having their own computers, avoiding the delays of time−shared machines. A typical workstation was a Sun−3, costing about $10,000, and providing about 1 MIPS.

By 1990, entire careers had passed in the frozen winter of 1−MIPS computers, mainly from necessity, but partly from habit and a lingering opinion that the early machines really should have been powerful enough. In 1990, 1 MIPS cost $1,000 in a low−end personal computer. There was no need to go any lower. Finally spring thaw has come. Since 1990, the power available to individual AI and robotics programs has doubled yearly, to 30 MIPS by 1994 and 500 MIPS by 1998. Seeds long ago alleged barren are suddenly sprouting. Machines read text, recognize speech, even translate languages. Robots drive cross−country, crawl across Mars, and trundle down office corridors. In 1996 a theorem−proving program called EQP running five weeks on a 50 MIPS computer at Argonne National Laboratory found a proof of a boolean algebra conjecture by Herbert Robbins that had eluded mathematicians for sixty years. And it is still only spring. Wait until summer.”

I don’t know for sure, but I suspect most of my readers, including yours truly, are “AGI Atheists” (or maybe “AGI Agnostics”), but going through Moravec’s decade old essays did make me wonder whether my non-belief is actually on shakier grounds than believers’ belief on the compute theory of everything! The religious fervor of summoning “God” into data centers seems ridiculous at first glance, but maybe “summer” is almost here!

In addition to “Daily Dose” (yes, DAILY) like this, MBI Deep Dives publishes one Deep Dive on a publicly listed company every month. You can find all the 65 Deep Dives here

Current Portfolio:

Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.

My current portfolio is disclosed below: