The Appeal of Cash

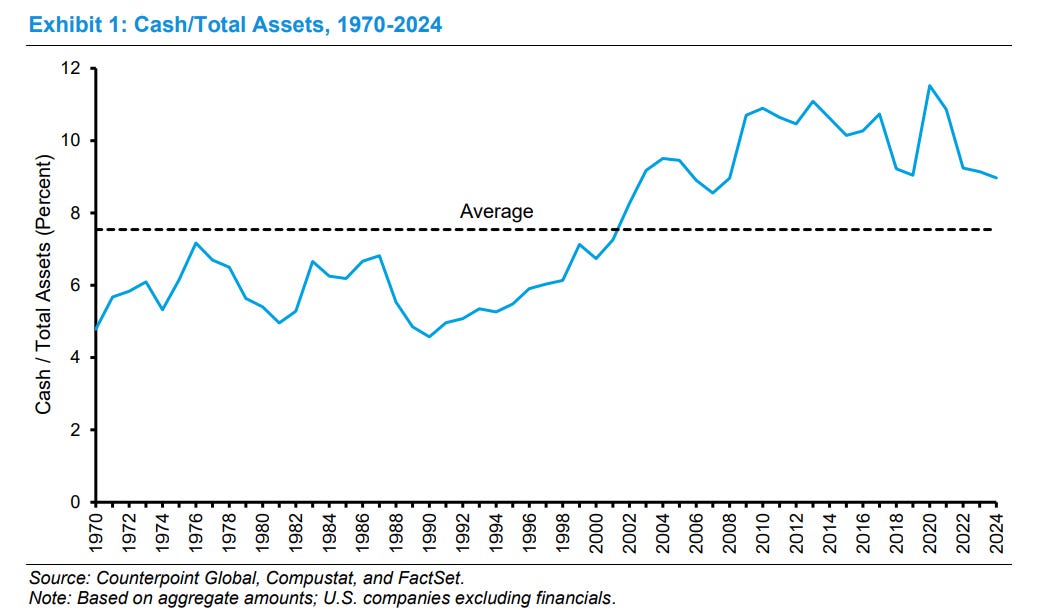

Last month, Michael Mauboussin and Dan Callahan published a report on history and implications of cash holdings among publicly listed companies in the US. Excluding financial firms, US companies had $2.5 Trillion cash at the end of 2024 (4.7% of total market cap). From 1970 to 2000, the average ratio of cash to total asset was 5.8%, but it has increased to 9.7% during 2001 to 2024 period.

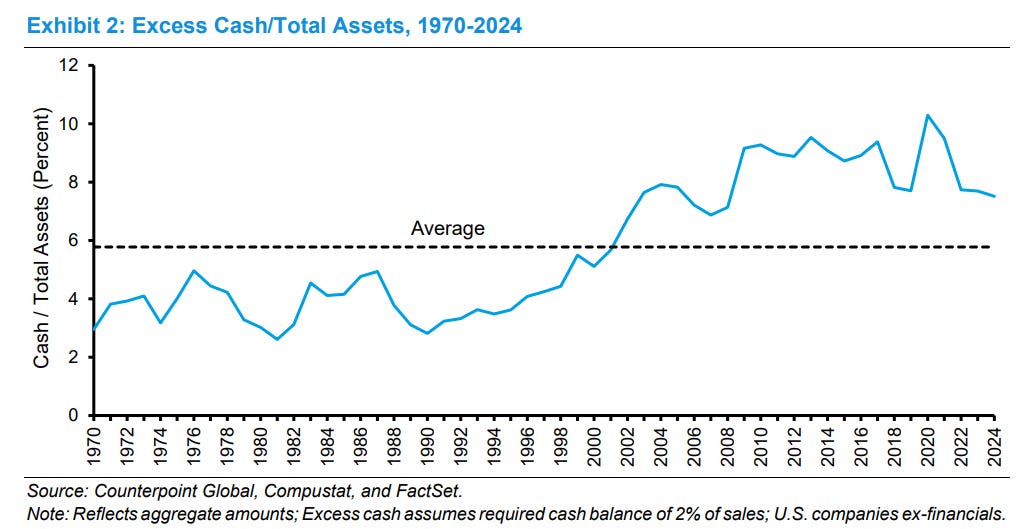

Of course, you need some cash to run the business on a day-to-day basis. If we assume 2% of sales is what you require to operate the business and define anything above 2% of sales as excess cash, we can see the chart still shows more or less the same picture. US companies didn’t have much excess cash for much of 1970s and 1980s, but post-2000s, they seem to want to operate with much more excess cash.

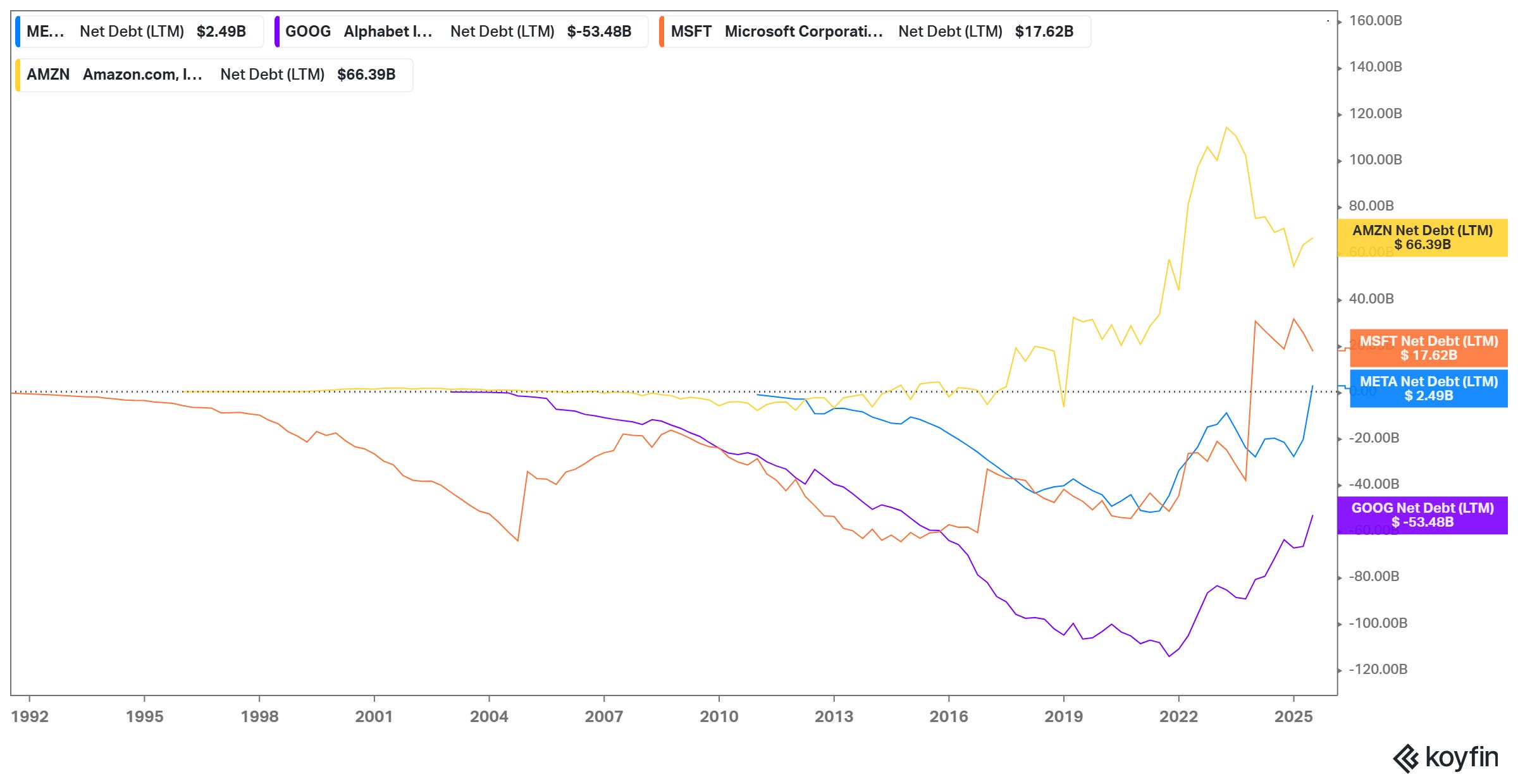

Big Tech almost consistently run their business with net cash. Perhaps the shadow of the dot com bubble still looms so large in their minds. It is worth remembering that Amazon was tantalizingly close to go out of business; thankfully, Amazon’s then CFO who was advised by Ruth Porat (Alphabet’s penultimate CFO) to raise some cash as the internet mania was almost at its peak. Brad Stone’s book “The Everything Store” mentioned this chilling story (emphasis mine):

“While other dot-coms merged or perished, Amazon survived through a combination of conviction, improvisation, and luck. Early in 2000, Warren Jenson, the fiscally conservative new chief financial officer from Delta and, before that, the NBC division of General Electric, decided that the company needed a stronger cash position as a hedge against the possibility that nervous suppliers might ask to be paid more quickly for the products Amazon sold. Ruth Porat, co-head of Morgan Stanley’s global-technology group, advised him to tap into the European market, and so in February, Amazon sold $672 million in convertible bonds to overseas investors. This time, with the stock market fluctuating and the global economy tipping into recession, the process wasn’t as easy as the previous fund-raising had been. Amazon was forced to offer a far more generous 6.9 percent interest rate and flexible conversion terms— another sign that times were changing. The deal was completed just a month before the crash of the stock market, after which it became exceedingly difficult for any company to raise money. Without that cushion, Amazon would almost certainly have faced the prospect of insolvency over the next year”

I imagine Amazon (and others) in hindsight inferred that while they survived, it was always unacceptable to be in such a position in the first place. They should have comfortable cushion long before the music stopped.

I don’t necessarily interpret this as some sort of “cultural” preference for robust cash position among tech companies though. There are actual constraints which sort of forced them to run their business with net cash position. Mauboussin and Callahan wrote:

The most important driver of the increase in cash holdings appears to be the growth in intangible relative to tangible investments

The basic idea is that intangible assets have limited value as collateral, which caps the debt capacity of those companies reliant on them. Further, many of these companies have good prospects for growth and do not want to be subject to the vagaries of capital markets or economic shocks.

Indeed, now that big tech have lots of tangible capital and will almost certainly increase tangible capital much much over the course of this decade, they are increasingly much more active in debt markets. If scaling law persists, it is probably not even controversial to expect that all of the big tech (except Nvidia and Apple) will likely have material net debt on their balance sheet by 2030. Although these happened for different reasons, Meta (buyback+ capex), Microsoft (Activision acquisition), and Amazon (both retail and AWS capex spree) already saw material shift in their net cash position. While Google’s net cash position has also declined noticeably in the last three years, Google remains the only company in the AI race with a $50 Billion+ net cash position.

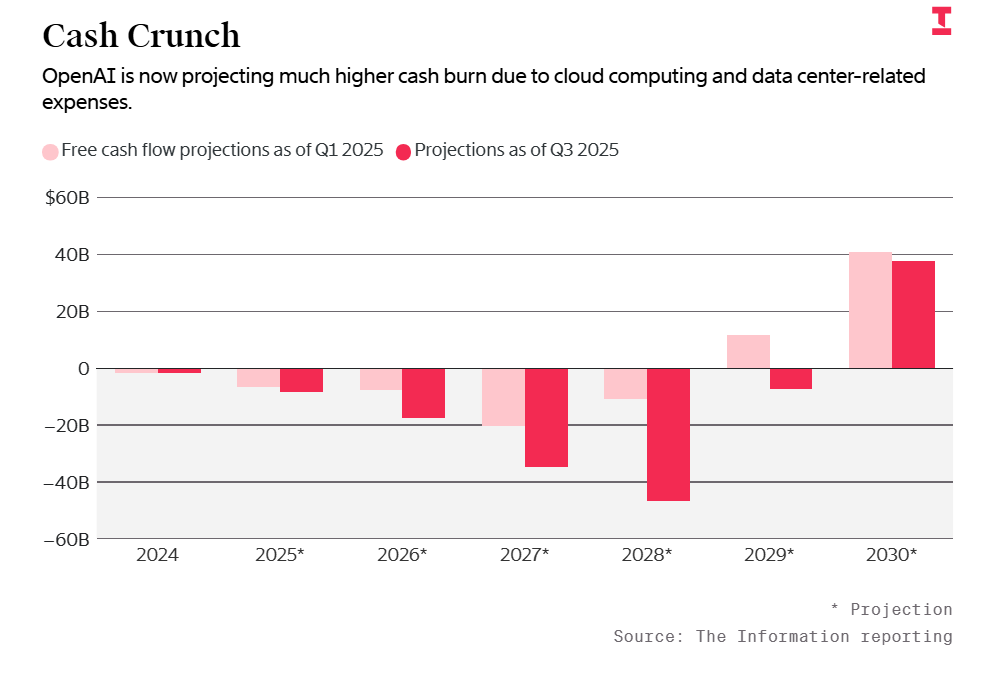

From Google’s perspective, that’s a pretty neat position to be in given the capex requirement in the AI race, especially when your primary threat OpenAI just allegedly let their investors know their cash burn would be $80 Billion higher than expected for the rest of this decade. From The Information:

OpenAI projected its cash burn this year through 2029 will rise even higher than previously thought, to a total of $115 billion. That’s about $80 billion higher than the company previously expected.

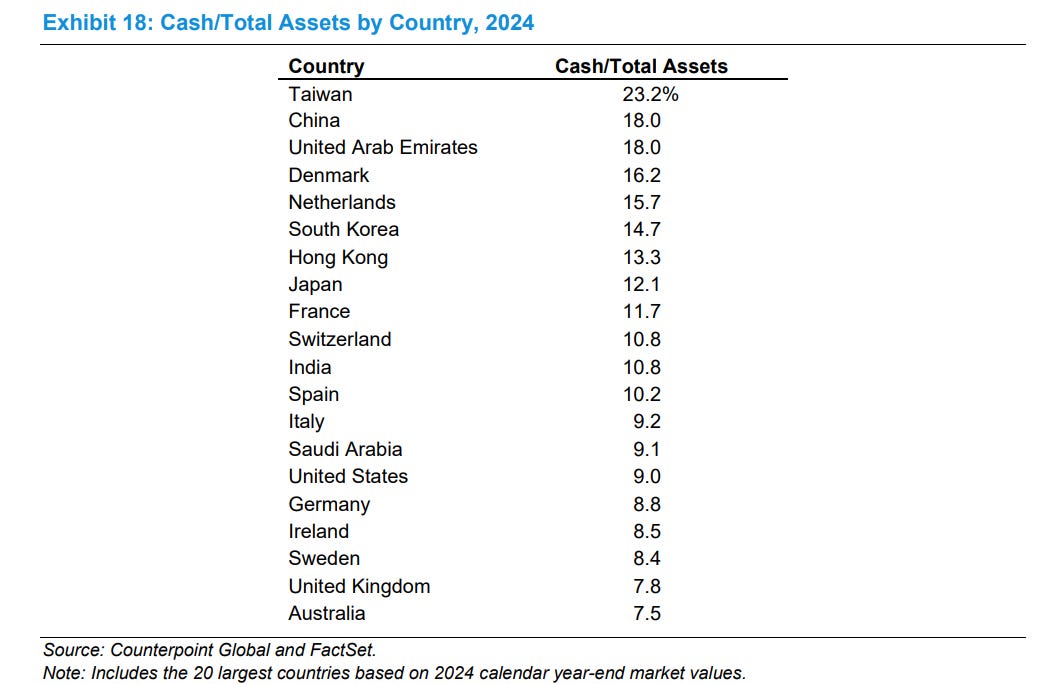

The appeal of cash actually appears to be much stronger outside the US. Mauboussin and Callahan showed the below country comparison and US public companies are actually nowhere near the top. Of course, cash becomes the most prized asset during period of extreme volatility. I remember back in Covid, Keyence boasted they could survive 17 years without ANY revenue! While that might have been comforting during Covid, that seems bit of an overkill. Of course, hoarding cash is no free lunch; it has very real opportunity costs. There is bit of a conflict of interest between shareholders and management here. Mauboussin and Callahan explained:

“Broadly speaking, companies generally want to hold more cash than investors want them to. Investors prefer less cash because they commonly hold the stock of a company within a diversified portfolio and prefer that management focus on building long-term value per share. Executives prefer more cash because it generally reduces their idiosyncratic risk and increases their ability to make decisions that benefit them and not necessarily their shareholders.

In this context, the main risk shareholders face is that of executives using corporate resources for their benefit at the expense of the shareholders.”

The last thing I want to highlight is the report mentioned “there is research that suggests cash-rich companies are more likely to do acquisitions and that they often fail to create value”. Lina Khan’s FTC was certainly an impediment for big tech to go for large deals; while I wouldn’t say current FTC is friendly to big tech, the current administration appears to be in a “cozier” relationship with big tech. As they say, “be careful what you wish for”; now that big tech has found a “loophole” to acquire companies (see Windsurf, ScaleAI, Inflection acquisitions etc.), I actually wonder if such a permissive environment would prove to be more value destructive for shareholders in the long run.

In addition to "Daily Dose" (yes, DAILY) like this, MBI Deep Dives publishes one Deep Dive on a publicly listed company every month. You can find all the 62 Deep Dives here.

Current Portfolio:

Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.

My current portfolio is disclosed below: