Perimeter: Private-Equity GP Economics in Public Markets

You can listen to this Deep Dive here

It wouldn’t shock me if the word “SPAC” itself has a negative connotation in your mind, but of course, it doesn’t inherently imply anything nefarious. A SPAC or “Special Purpose Acquisition Company” is just a publicly traded shell corporation that raises capital through an IPO to merge with or acquire a private business, enabling that target to become publicly listed without undergoing its own traditional IPO.

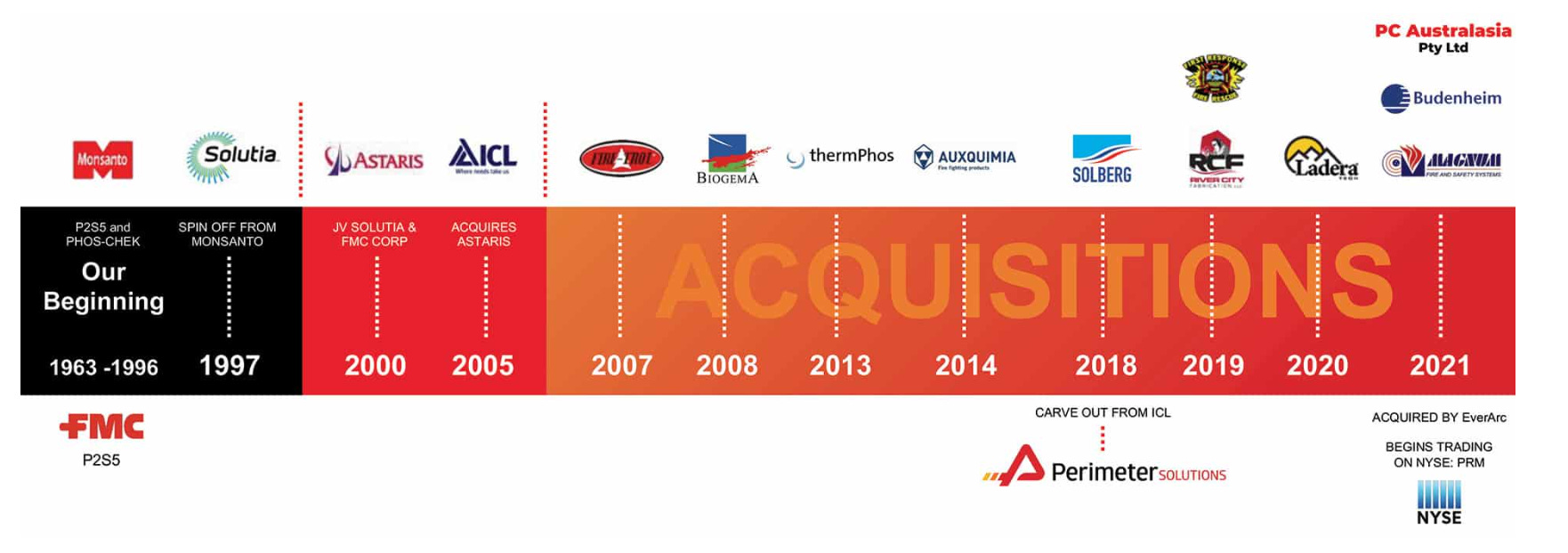

EverArc Holdings, an acquisition company listed in London in December 2019, raised ~$340 million and staffed its board with some heavy hitters: TransDigm co-founder Nick Howley, “Outsiders” author-investor Will Thorndike, and Berkshire alumna Tracy Britt Cool, among others . EverArc had the mandate of building a platform that can let public shareholders enjoy “private-equity-like returns with the liquidity of the public markets”.

I kind of find it amusing how that’s supposed to be appealing. What percentage of PE or VC firms actually generated higher returns than S&P 500 in the last 10-15 years? If you read between the lines, EverArc people are alluding private equity has better return profile than public equities and they would like to “democratize” this elusive return profile to random Joe out there.

The reality is, of course, that a small minority of investors in all asset classes will be able to beat the public equity benchmark index such as S&P 500 over the long-term. While Warren Buffett rightly receives a lot of adulation, the average Joe out there really should be much more grateful to Jack Bogle for truly democratizing investing vehicle such as S&P 500; it may not be a stretch to even claim that Jack Bogle may have sowed the seed to create many more millionaires than any active investor out there, including the GOAT Buffett!

So, the talk of “private-equity-like returns with the liquidity of the public markets” is mostly a sales pitch. However, if we look beyond this sales pitch, EverArc did have a solid approach in finding a potential target.

EverArc sifted through more than 200 prospects, scoring each against five economic filters it considered non-negotiable: revenues that recur with high visibility; an industry enjoying secular tailwind; products that cost a rounding error to customers yet mission critical; free-cash-flow margins and returns on tangible capital that leave room for error; and a landscape ripe for bolt-on acquisitions.

While I don’t quite think Perimeter ticked every box, its business does have compelling characteristics.

Perimeter’s primary business revolved around making long-term fire-retardant chemicals that are mixed with water and dropped from planes, helicopters, or applied from the ground to coat vegetation and structures ahead of a blaze. The phosphate-based solution, which is tinted bright red so pilots can see their coverage, changes how cellulose burns, effectively rendering grasses, brush, and timber non-flammable. A common misperception is that those vivid aerial drops extinguish fires on contact, when they really just delay the flame’s advance until ground firefighters can secure control lines.

How did this business meet EverArc’s stringent criteria?

Wildfire seasons, amplified by climate volatility, provide the secular tailwind. Although it is impossible to predict any particular year’s revenue in this business given somewhat fickle nature of severity of wildfire season from one year to another, the long-term decadal trend is one way street. As a result, you may have very limited visibility from year-over-year perspective, but can potentially be more confident about decadal trajectory. It is one of those rare businesses that may be easier to predict 10 years out than to guess next year’s revenue.

Retardant and additive purchases are indeed a rounding error in government firefighting budgets, yet determine whether an advancing fire front is checked or rages on. Based on six decades of operational history, we know this business demonstrated extremely sticky customer retention. The business changed many hands over the decades, and while there is plenty of volatility in revenue and margins from one year to another, the business model boasted strong EBITDA margins with low capex requirements over the longer term. It also certainly helped that Perimeter had an absolute monopoly in fire retardant industry.

Like most other SPACs, Perimeter had quite a tumultuous couple of years since becoming a public company. While Perimeter came to the public market with the narrative of an absolute monopoly and resultant high margin, investors became quite wary when they came to know about a new entrant which threatened Perimeter’s “private equity-like return”. Ultimately, while “private equity-like return” is far from guaranteed, the only reality for any public company is volatility. The real “moat” for private equity is not perhaps in the actual returns, but in their magical ability to mask volatility. Indeed, Perimeter’s stock precipitously fell by ~75% by November 2023, but as the competitive dynamics largely turned out to be bit of a false flag, the stock has rebounded and nearly come back to its IPO price.

While fire retardant remains the most important segment for Perimeter today, it is ~60% of their revenue today. So, let’s take a much closer look at their current businesses and a more granular understanding of the industry tailwinds as well as economics of the business. That’s section 1.

In Section 2, I will discuss how Perimeter was able to maintain their monopoly in fire retardants for decades and some potential risks that can potentially hinder their dominance.

In Section 3, I will elaborate on Perimeter’s capital allocation philosophy. Moreover, Perimeter’s incentive structure deserves to be unpacked in greater detail than usual which is the key focus on this section.

In section 4, I will show what is likely currently embedded into the stock price. Finally, I will offer some concluding thoughts and disclose my overall portfolio. Subscribe to keep reading!