Music's AI mess

Most of you may not have heard about Xania Monet, but “she” created a bit of a stir in the music industry last month when Hallwood Media, an independent music label company, signed a $3 million deal with her as her new track “How Was I Supposed To Know” reached No. 1 on Billboard’s R&B Digital Song Sales chart. She is no one trick pony either as another song “Let Go, Let God” currently number 3 on Hot Gospel Songs chart.

Why is this a big deal? Well, Xania Monet is NOT a real person!

Monet is an AI-generated virtual R&B persona. The vocals and the instrumental music released under the name Xania Monet are created using the AI music generation platform Suno. The lyrics are written by a human creator, Telisha “Nikki” Jones, a poet and designer based in Mississippi. Jones writes poetry drawn from her personal experiences and then inputs those lyrics into the Suno platform. Suno then generates the melody, instrumentation, and the vocal performance to create the finished track.

If we define “AI artist” strictly as an artist whose music and/or vocals are primarily created using generative AI tools (like Suno or Udio), Xania Monet appears to be the first to achieve such significant success on the US Billboard charts. I doubt that she will be the last artist.

Interestingly, while a label signed Monet (or should I say Telisha Jones since she’s the person behind Monet), there has been an ongoing lawsuit between the labels and AI-based music generation platforms.

In my UMG Deep Dive last year, I highlighted this tension between these two parties:

“The record labels’ primary arguments against Suno revolve around copyright infringement and the improper use of copyrighted music to train its AI models. The labels claim that Suno has engaged in “mass infringement” by using their copyrighted sound recordings without permission to develop and train its music-generating AI. The labels further mention that Suno’s activities violate copyright law because the AI-generated songs are based on pre-existing recordings, and no licenses or permissions were obtained for this usage.

Suno’s main argument against the lawsuit filed by major record labels revolves around the issue of fair use. Suno acknowledges that its AI models were trained on publicly accessible music, including songs owned by these labels, but argues that this use falls under the fair use doctrine. Suno claims its AI systems do not directly copy the music but rather learn from it in a way similar to how humans learn from existing works.

Labels, of course, reject Suno’s fair use defense, arguing that fair use applies to limited, transformative scenarios involving human creativity, not machine-generated content that mimics or dilutes the value of original music recordings.

How this lawsuit will be settled is above my paygrade”

But can Monet’s songs be copyrighted?

Because the lyrics are written by Telisha Jones, they are protected by copyright. The US Copyright Office allows the use of AI as an “assistive tool,” but may not grant copyright protection if “AI technology, and not a human, determines the expressive elements of the output.” The legal uncertainty lies in the copyright status of the final sound recording i.e. the combination of human lyrics and AI-generated music and vocals. The extent to which the AI-generated elements are protected remains legally untested.

UMG in the last earnings call put a brave face and emphasized that their agreements with DSP partners such as Spotify will be sufficient in curbing the proliferation of AI generated music and diluting labels’ share of the profit pool. From UMG management:

“…AI models will not be trained on our artists work without consent. AI recording to train on our content will be removed. AI-generated music will not dilute our artist royalties and AI content that misappropriate our artist identities and infringes upon their right of publicity will also be removed. And various monitoring requirements are also included in these agreements.”

UMG also mentioned how consumers themselves don’t really want to listen to “simulation or imitation of artists”:

“We talked to consumers about their interest in AI and music. 51% of U.S. consumers expressed interest in AI integration and music, but half of those really wanted to focus AI integration to improve their music consumption experience, meaning better recommendations, better discovery, better content interaction.

Of the various AI music categories, I don’t think anyone will be surprised to hear that simulation or imitation of artists rank the lowest. And there’s tremendous interest by consumers in a connection to the artists. I mean we kind of define that as a moral code, where 75% of these consumers interested in AI said, they believe that human creativity is essential. A similar percentage, say, connection to artists is key to their interest, and this is consistent across age groups.”

While UMG may think there is a consumer distaste to AI slops, Monet’s success should make them rethink a bit. I do think the general attitude to “AI slop” is a bit misguided; I believe people has aversion to “slop” in general regardless of whether AI or a human is behind it. Similarly, a good song may just be a good song and if history is any guide, our “moral code” can evolve with the passage of time.

It’s interesting that Verge mentioned Xania Monet’s songs as “somewhat passable”. In fact, it wouldn’t surprise me if some of you clicked the songs (mentioned above) and snickered on “AI slops”. I am no music connoisseur, but I can tell you that as a listener, I did find “Let Go, Let God” to be quite compelling.

Perhaps more importantly, what if consumers simply cannot differentiate between AI generated and human crated music anymore? In fact, back in June 2025, there was a paper showing exactly that: people cannot seem to differentiate between AI generated music and music created by human artists; in fact, they increasingly like AI generated music more!

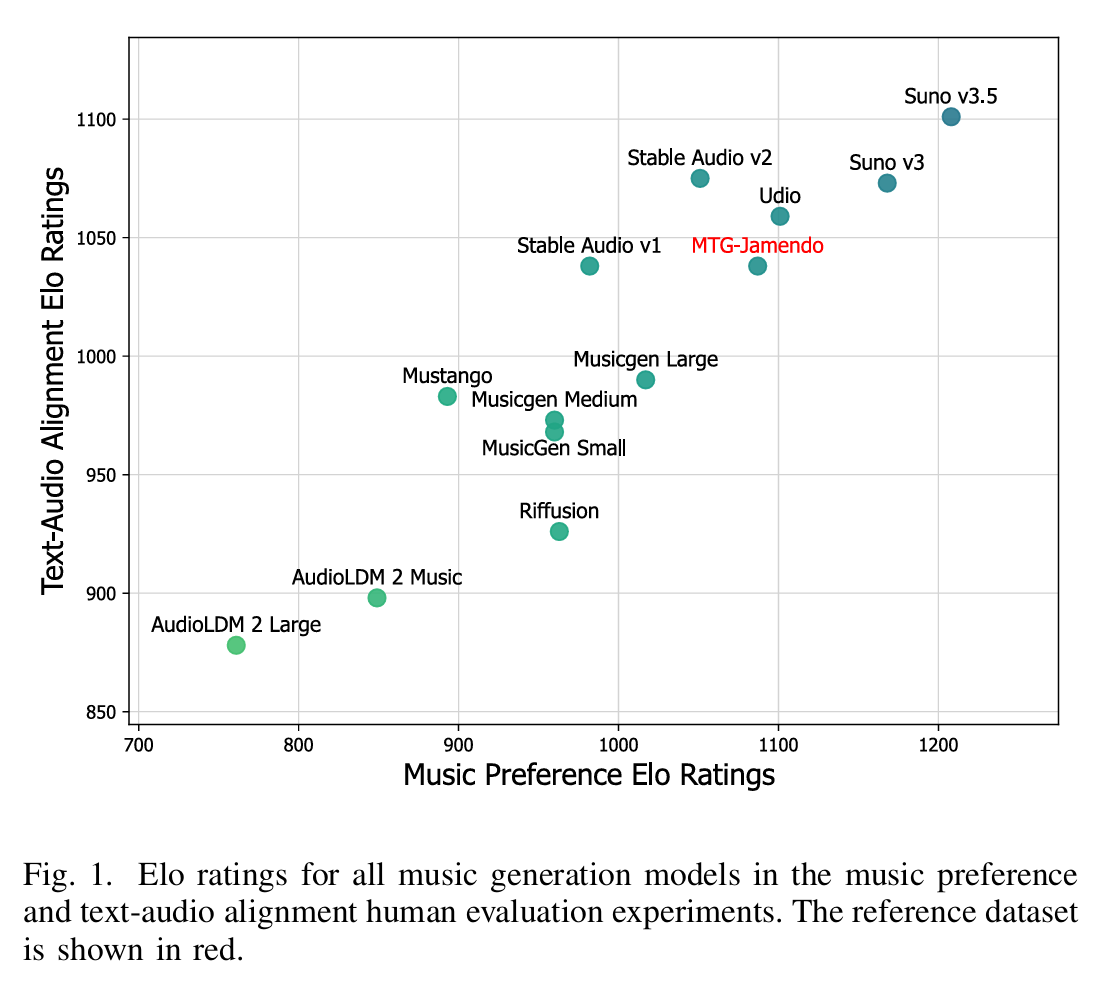

The researchers conducted a comprehensive benchmarking study. This involved generating a dataset of 6,000 songs using 12 state-of-the-art music generation models and then conducting a large-scale survey with 2,500 human participants, collecting over 15,000 pairwise audio comparisons to understand listener preferences and perceived text-audio alignment.

For music created by human artists, they used MTG-Jamendo which is a large library of real music created by human artists (containing 55,000 tracks). What makes it useful for researchers is that every song is labeled with descriptive tags detailing its genre, the instruments used, and the mood of the music. The researchers used it as a high-quality standard for human-made music to see if the AI-generated compositions could measure up or even surpass it.

To evaluate different models, they used the Elo rating system which is a scoring system used to calculate the relative skill levels of competitors in head-to-head matchups; it is typically used to rank chess players and sports teams. In this study, the “competitors” are the different AI music models.

The system works by comparing two models at a time. When a human participant listened to two songs and preferred the song by Model A over the song by Model B, Model A “won” that matchup. When a model wins, its Elo score goes up; when it loses, its score goes down. After thousands of these comparisons, the final Elo ratings provide a clear ranking of which AI models consistently produced the music that people liked the most.

The human evaluations established a clear ranking of the models, revealing that commercial systems currently dominate the field. Specifically, Suno v3.5, Suno v3, and Udio demonstrated superior performance, even outperforming the human-created MTG-Jamendo reference dataset in terms of listener preference.

While this paper used Suno v3.5, Suno recently launched v5. You can imagine v5 might have scored even higher in this paper. Not only this seems to be one-way street from here, the SOTA model folks are also showing strong interest in getting into action. From The Information:

“OpenAI staff have been taking steps to develop AI that generates music, according to a person with knowledge of the work. For instance, the company has been working with some students from the Juilliard School to annotate music scores, according to a second person. They are providing the kind of training data that would be needed to develop AI that produces music.

OpenAI has privately discussed generating music with text and audio prompts: for example, enabling people to ask the AI to add guitar accompaniment to an existing vocal track, according to a third person who has been involved in the discussions. The resulting product could also help people add music to videos.

If OpenAI releases a music-generating tool, that could help the company’s own expansion into advertising someday. An ad agency, for instance, could use OpenAI’s tools for tasks related to generating an ad campaign, such as brainstorming ideas for lyrics, creating a catchy jingle based on music samples or recordings, or uploading a video to mimic in terms of style, according to one of the people.

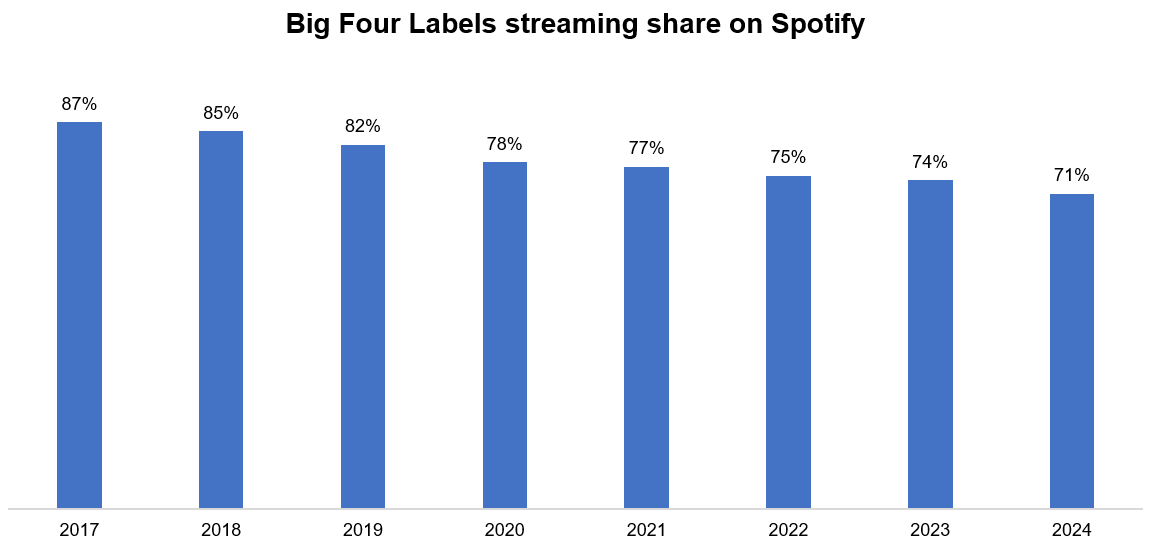

Even if wholly AI generated music is deemed outside the purview of copyrighted content, it is extremely likely that supermajority of human artists will utilize these tools to increase the pace of their own output. While a Cambrian explosion of AI generated or AI assisted music may not be a drastically different reality than the status quo for DSPs such as Spotify, such a deluge of content may accelerate the dilution of major labels’ share over time.

In addition to “Daily Dose” (yes, DAILY) like this, MBI Deep Dives publishes one Deep Dive on a publicly listed company every month. You can find all the 64 Deep Dives here.

Current Portfolio:

Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.

My current portfolio is disclosed below: