GDP's absurdity

When I read the following excerpt from the book “Poor numbers” last year, it was a stark reminder of lack of state capacity in many parts of the world even for collecting some routine data:

In 2010, I returned to Zambia and found that the national accounts now were prepared by one man alone… Until very recently he had had one colleague, but that man was removed from the National Accounts Division to work on the 2010 population census. To make matters worse, lack of personnel in the section for industrial statistics and public finances meant that the only statistician left in the National Accounts Division was responsible for these data as well.

Coming from Bangladesh, I was well aware that it is hard to rely on statistics produced by the government. While that lack of trust often came from lack of integrity in the process, I realized I didn’t put as much weight as I should have on many countries’ lack of resources to even collect, organize, and report the data.

However, after reading “How GDP Hides Industrial Decline” by Patrick Fitzsimmons (former founding engineer at HubSpot), I am starting to entertain the idea that at least in case of GDP, it may be an impossible task even if you have plenty of resources and no apparent desire to “game” the numbers.

Like the author, I too have read that US manufacturing output has continued to go up over the last few decades even though labor’s share of manufacturing jobs kept going down primarily due to automation. Unlike the author, I never quite questioned this conventional wisdom. However, when he took a peek under the hood, it didn’t appear that such “wisdom” is based on strong foundation.

To understand the flimsy nature of such belief, we first need to understand the nuances around calculating GDP:

Discourse over GDP is frequently confused because there are actually three different calculation approaches: the income approach, the expenditures approach, and the value-added approach.

Each approach has its uses, but you have to be careful with which you use. What percent of GDP is healthcare? You get two different numbers depending on the approach. With the expenditures approach, healthcare is 17% of GDP, but for the value-added approach only 8%. Why? Because the value-added approach only counts expenditures on hospital and clinic workers toward the healthcare category. Money spent on manufacturing medical devices counts as manufacturing; money spent building hospitals counts as construction. For measuring healthcare’s share of the economy, it is probably better to use the expenditures approach because it is reasonable to include pharmaceutical production and hospital electricity bills as part of healthcare.

GDP is a very complicated statistical construct that is made by government bureaucrats behind closed doors without any ability of the public to replicate, audit, or verify assumptions. Sometimes, these kinds of constructs can be useful for accurately representing real-world phenomena, like manufacturing capacity. But a dive into how the sausage is made makes clear that GDP is not one of them.

So, how is the sausage made here? It is particularly striking to take a look at manufacturing:

If you want to see what percent of the economy is manufacturing, and how that has changed over time, you can only use the value-added approach. Only the value-added approach separates out each step in the economic chain: from mining the iron ore to transporting it to the factory to manufacturing the product to selling it at the store. The value-added approach categorizes each step, so you can sum together just the increase in price from the manufacturing step across all categories of spending.

Why is that a problem? The below example should make it abundantly clear that while we may look at very tangible looking number such as manufacturing output, we actually have very little clue about what the number even means:

let’s say that, in 1997, car sales were $100 billion, and were still $100 billion twenty years later in 2017, with no changes due to inflation or input costs. Input costs in both years were $75 billion, meaning $25 billion in value-added in both years. The only thing that changed, let’s say, was that the “quality” of cars got 10% higher thanks to software innovations like Apple CarPlay and design improvements like crumple zones for safety—neither of which add to recurring production input costs. So, let’s say, our economists would adjust the 2017 figure to be $110 billion in “real” terms and show a small 10% increase, right?

Instead, the way it works is that a recent “base year” is taken, in this case 2017, and the base year is never adjusted. So rather than adjusting from $100 billion to $110 billion, the “real” output of 1997 is retroactively adjusted to be lower, in this case $91 billion, to get the same 10% increase. But then, our value-added in 1997 has fallen to $16 billion, and the increase in “real value-added manufacturing” has jumped from 10% to around 50%! We have created a 50% increase in car manufacturing not by actually producing 50% more cars or “objectively” making cars 50% better, but just by playing around with statistics and definitions.

The effect becomes even more extreme as the quality adjustment gets higher and makes the original value-added shrink to zero or negative. If the quality adjustment is 32%, the value-added increase becomes 652%! And after that it goes infinite and then becomes undefined. Of course, there are further complications. If the inputs are quality-adjusted in the same way as the outputs, the effect might be less, but this probably won’t happen because the methodology is quite different. This is all to demonstrate that value-added is not a measure of how much stuff the United States makes. It is a number that produces wild results and thus should not be mixed into aggregate statistics.

I do not know if these scenarios described above are the actual reasons for why value-added is so greatly outpacing gross output. No one else knows either.

I almost felt bad for Zambia for having just one statistician to prepare some critical data related to National Accounts, but I don’t know how to feel about it after reading how the sausage is made even in the most advanced economies of the world. As much as we pay attention to GDP numbers, I’m not sure we actually understand what we are looking at most of the time.

While a lot of these concerns may be a feature rather than a bug, data quality concerns have also been affecting some other critical macro data as well. Take inflation, for example. From Apollo:

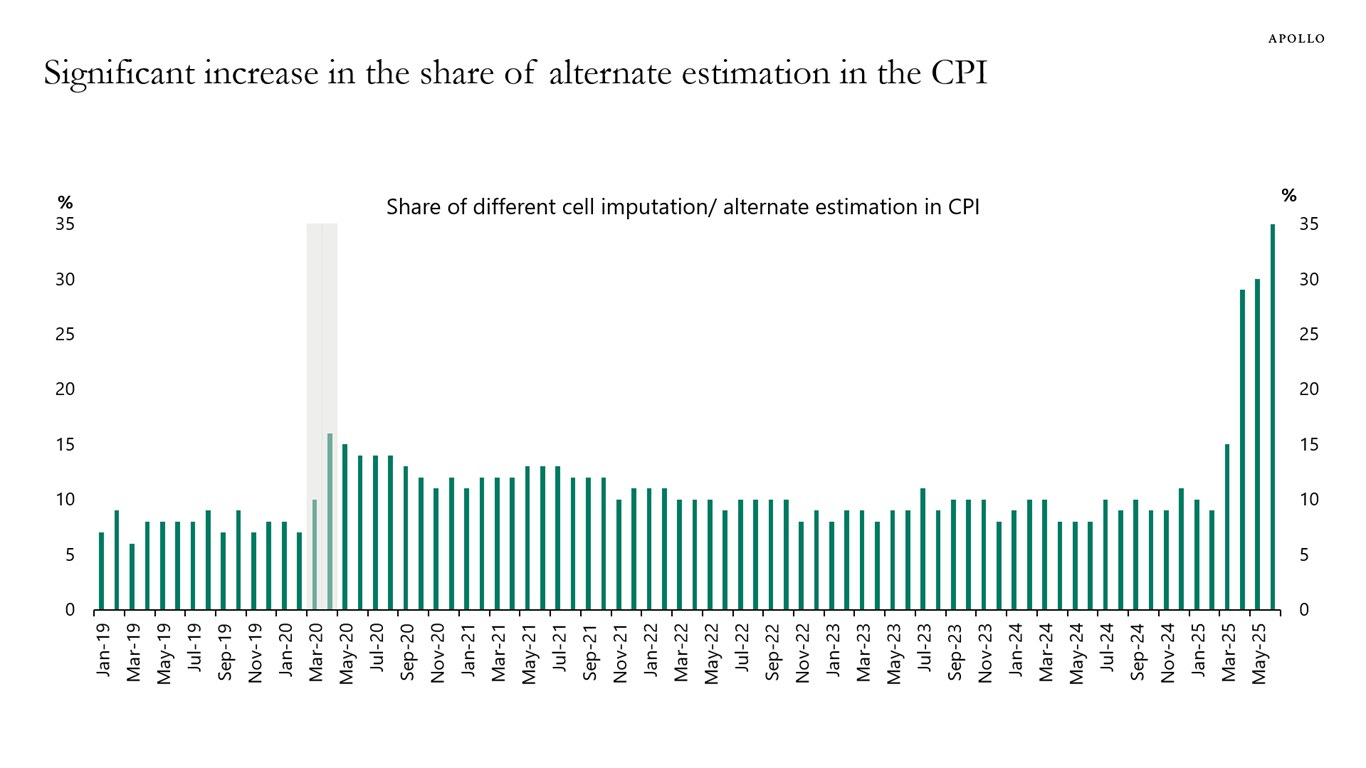

When data is not available, BLS staff typically develop estimates for approximately 10% of the cells in the CPI calculation. However, the share of data in the CPI that is estimated has increased significantly in recent months and is now above 30%, see chart below.

Looking at these data, it was just another strong reminder that it may not be worth spending a lot of time looking at macro data which are much more black box than we may think. It may be much more worthwhile to follow specific companies and try to form opinions about them; perhaps it may be relatively easier to create a mosaic of the economy through this bottom-up approach than the other way around. Of course, that’s not easy either, but at least, it may be less made up than the top-down approach.

In addition to “Daily Dose” (yes, DAILY) like this, MBI Deep Dives publishes one Deep Dive on a publicly listed company every month. You can find all the 63 Deep Dives here.

Current Portfolio:

Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.

My current portfolio is disclosed below: