Brown & Brown: A Decentralized, Boring, Money Making Machine

Disclosure: I am long shares of Brown & Brown

You can listen to the Deep Dive here

When I first read Leonard Read’s seminal essay: “I, Pencil”, it became abundantly clear to me that people who solve the co-ordination problem in capitalism are of paramount importance (if you haven’t or don’t have the time to read the essay, watch this Reels). At first glance, intermediaries that generate attractive economics for themselves by connecting seemingly unrelated vast network of people may be deemed leeches of capitalism, yet without the intermediaries, any innovation runs the risk of being siloed to just a few. It is perhaps, therefore, no wonder that intermediaries that prove their worth to the broader value chain often end up more insulated from the direct risks and enjoy a more stable and durable economics among all the players in such value chains. Brown & Brown is one such intermediary.

Brown & Brown (Ticker: BRO) is an insurance broker that sells insurance on behalf of the carriers to mostly small/medium sized businesses and gets paid largely a fixed percentage of commissions on the insurance premium without taking the insurance underwriting risk. Insurance brokers provide a valuable service to both parties: SMBs get access to brokers’ full breadth of relationships with multiple carriers as well as better price discovery, convenience, and expertise provided by the brokers. Hyatt Brown, current chair of the board and penultimate CEO of BRO, once mentioned, “..insurance policies are really the most complex contract that you'll ever enter into without the help of a lawyer”. Carriers, on the other hand, can leverage brokers’ presence in the ground and direct relationships with businesses to scale their insurance products much more efficiently.

Insurance broking has a long history in the US. Marsh McLennan, the market leader in this industry, was founded in 1905. Brown & Brown’s founding root was initiated in 1939. Jay Adrian Brown, who is the father of Hyatt Brown, and his first cousin CC Owen founded an equal partnership in Daytona Beach, Florida. Brown & Owen eventually became today’s Brown & Brown when Jay Brown’s elder son joined the company. After graduating from University of Florida, Hyatt Brown (the younger son), also joined the company in 1959. But just two years later, Hyatt ended up being the CEO of the company. Why?

Hyatt’s brother was appointed the chairman of the Florida Industrial Commission and hence had to resign from BRO. At the same time, Jay Brown decided to retire at the age of 65.

In 1961, BRO generated ~$61k in revenue and $1.4k in profit. Jay wanted to sell the company to Hyatt for $75k. The only problem was Hyatt, having only graduated college two years ago, didn’t have the money to buy. So, Jay made a deal with his younger son: Hyatt would have to pay 10% interest of $75k for both Jay and his wife’s (Hyatt’s mother) lifetime.

By 1972, Brown’s revenue increased to $345k, so Hyatt was clearly doing more than a decent job as CEO. But someone apparently dared him to run for the legislature and he accepted the challenge in 30 seconds. He won by a whisker and sat in the Florida House of Representatives, as a Democrat, from 1972 to 1980. Hyatt then returned to Brown and outlined a plan to double the revenue organically by 1982 from $2 mn to $4 mn. Brown was indeed able to meet the revenue target, but operating margin declined from 16% to 8% leading to pretty much similar profit despite doubling the revenue.

For the first time, Hyatt decided to call a consultant to take a look at his operating plan. The consultant carefully looked at Brown’s business and spoke with them three days later. He suggested while they were all great salespeople, they are not good at making money. Hyatt wasn’t offended because the consultant was right. Then the consultant indicated if they followed his recommendations, Brown’s organic growth would likely slow but their operating margin would reach 25%. Why did Hyatt take the consultant seriously? Because the consultant himself ran an insurance agency in upstate Michigan and showed Hyatt his numbers to substantiate how the numbers worked in his firm.

Hyatt took the consultant’s suggestions at heart and added a couple of twists on his own to outline Brown’s operating principles. From that initial experience, Hyatt codified the significance of making money as one of the four operating principles of Brown & Brown: “we are in the money-making business.”

In 1983, Hyatt created a new 7-year operating plan for BRO. Under the base case scenario, he expected BRO to reach $19 Mn revenue in 1990 (~21.5% CAGR from 1982) and $29.5 Mn revenue (~28% CAGR) in optimistic scenario; under either scenario, Hyatt wanted to ensure attractive margin for the company. In 1990, BRO posted $25.5 Mn revenue (~26% CAGR) with 24.5% operating margin.

Even though BRO wasn’t a public company back then, they operated almost like a public company. In the early 90s, BRO had ~25 shareholders, almost all of whom were employees at BRO. They even had an annual shareholder meeting. If anyone wanted to sell (a rare event), the company would just buyback the shares from the employee using a pre-specified formula(I don’t know what exactly the formula was). However, one of the shareholders suffered a heart attack and while he survived, he wanted to sell his stocks. The employee was given $700k worth of shares in 1980 which increased in value to $9.3 Mn in 1993. Hyatt decided to buyback the shares himself; but he also realized it is clearly not a sustainable solution. When the company buys back shares from the employees, it constrains the company’s ability to deploy capital to grow their business. As Hyatt was contemplating how to deal with this challenge, a solution arrived from an unexpected source.

One of Hyatt’s friends at Poe & Associates, a publicly listed company, approached him and suggested a merger between Poe and Brown. Poe had $52 Mn revenue in 1993 (vs Brown’s $33 Mn). Following the merger, Poe & Associates became “Poe & Brown”. However, just a year later, Bill Poe (the founder of “Poe & Associates”) left the company; while Hyatt and Poe had respect for each other, they differed in leadership style, as evidenced by Poe’s remarks: “He's a decentralist and I'm a centralist. He's more of a bottom-line-oriented manager, I'm more of a people-oriented manager. He's the hardest worker you've ever seen. He works about 70 hours a week.”

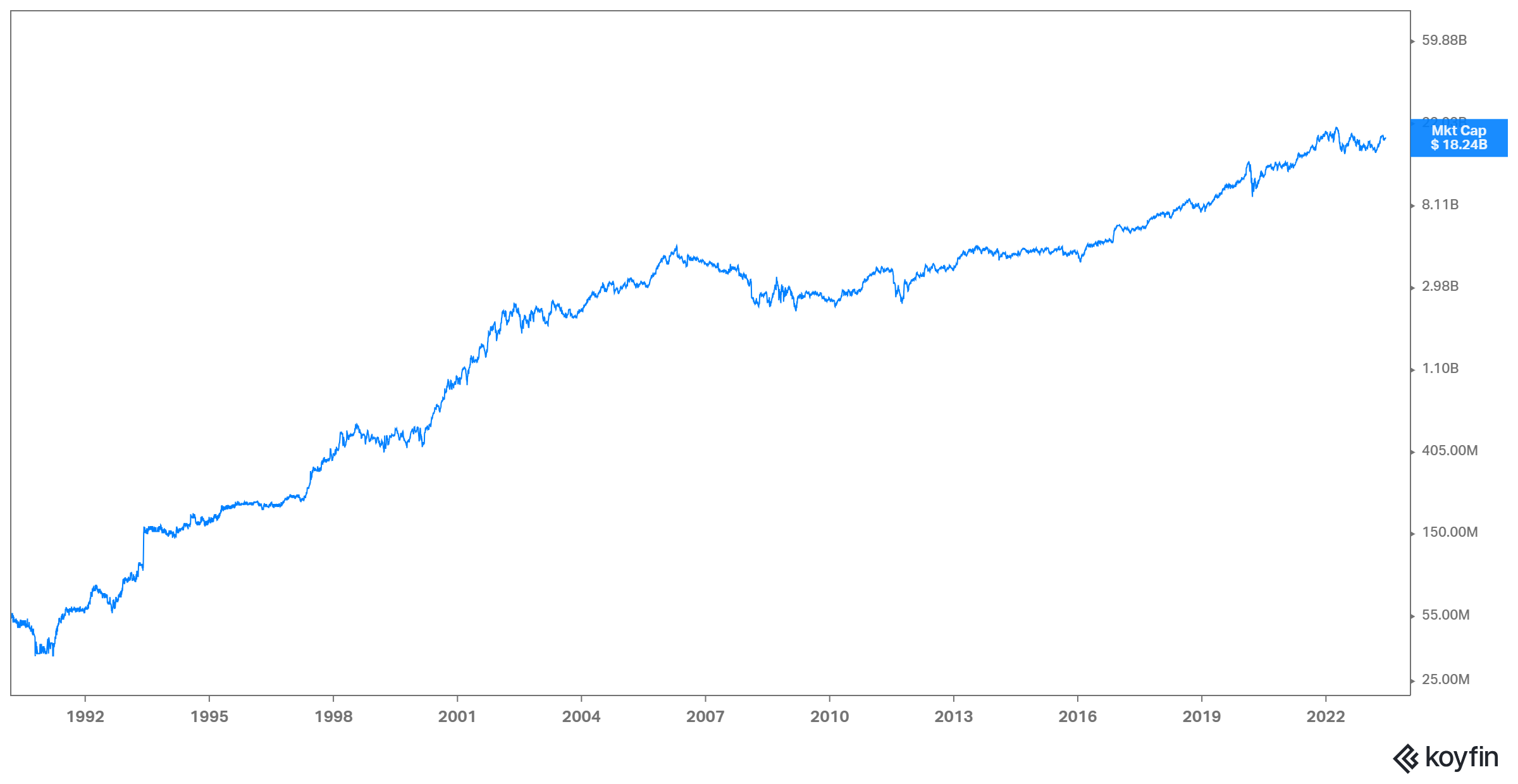

Poe was happy to let Hyatt run the company and by 1999, the shareholders voted “Poe & Brown” to become “Brown & Brown”. At the time of the merger in 1993, “Poe & Brown” had ~$55 Mn market cap. Today, “Brown & Brown” has ~$18 Bn market cap.

Here’s the outline for the rest of this Deep Dive:

Section 1 Operating Segments: I explained the basic business model of Brown & Brown and then delved into the economics of four operating segments: Retail, National Programs, Wholesale, and Services.

Section 2 TAM, Competition, and Acquisition Strategy: I discussed Brown & Brown’s Total Addressable Market, competitive dynamics, their acquisition history as well as their acquisition strategy in this section.

Section 3 Capital Allocation and Management Incentives: Management’s capital allocation history over the last two decades and their current incentive structure is highlighted here.

Section 4 Valuation/Model Assumptions: Model/implied expectations are analyzed here.

Section 5 Final Words: Concluding remarks on Brown & Brown, and disclosure of my overall portfolio.