Speedwell and MBI discuss Meta Platforms

Last week, Speedwell Research, an independent investment research service, published their Deep Dive on Meta Platforms. They were kind enough to send me a copy of their work. After reading their work, we exchanged a few emails/tweets discussing their report. I enjoyed this interaction enough to think I would like to keep our exchanges on Meta as a separate post on my website.

Click here to read Speedwell's work on Meta

Hope you enjoy our exchanges on probably one of the most hotly debated companies in the market! (slightly edited for clarity)

My initial email to Speedwell

First of all, thank you for sharing your work on Meta with me. I skipped your 16-page PM summary and took my whole Saturday to read your 166-page report (a “book” would perhaps be more appropriate). As a shareholder of Meta, I feel it was time very well spent. Despite following the company for almost 5 years, I learned new things from your work. Appreciate your (and your team’s) thorough, diligent, and unjaundiced work on a company that certainly elicits strong emotion among investors. Let me share some of my thoughts after reading your work.

“Enemy of the State”: I chuckled a bit when I saw Mark Zuckerberg jovially mentioned himself as “Founder, Master and Commander, Enemy of the State” on the “About” page of “Thefacebook”. Although it is more of a testament to the teen hubris, it is ironic how prescient that would be in terms of popular perception in the West.

“Radical Transparency”: I knew Zuckerberg’s penchant for radical transparency and how he erred on the “Beacon” fiasco, but I think people generally underestimate how principled Zuckerberg seems to be. Just today, I read this interview of a former Meta executive who touched on Meta’s culture of radical transparency: “When this period of the history of Silicon Valley is written, there will be at least one story about how radical Facebook’s internal culture of openness and transparency was, especially compared to the incredibly siloed & secretive cultures of Snap, Apple, and others. The openness at Facebook made it a fascinating place to work & helped it attract brilliant people. I think it made it a better company by fostering collaboration. But that openness also made it vulnerable and had some material downsides for the company.”

Scaling culture is perhaps one of the most challenging things founders need to do, especially for a large company such as Meta. With ~80k employees today, I do wonder whether it is time for Meta’s culture to evolve a bit. It is hard to change culture overnight, so perhaps they may need to learn to live with radical transparency.

Infrastructure as a moat: I never spent much time on why/how Friendster failed. I probably wouldn’t have guessed their poor infra investments were a dominant factor. It also perhaps provides much more context to Meta’s massive proprietary investment in data centers and infrastructure in general, and not be overly reliant on public cloud to a run a business used by the whole world. Companies who are going in the opposite direction may run the risk of becoming “Friendster” of the future. Zuckerberg’s formative experiences probably informed him deeply to make these infra related investments. To quote from your piece:

“Far from a trivial factor, page load time was hindering Friendster and, retrospectively, was one of the larger factors that led to their eventual irrelevance. Users were complaining of page load times of up to 40 seconds, with 20 seconds being not unusual. Such a poor user experience was driving users away.

Zuckerberg was far more methodical than his social networking peers, controlling Facebook’s growth until their servers were ready to handle the demand”

The relentless death march of Meta’s new standalone apps: Camera, Poke, Slingshot, Paper, LifeStage, Riff, Threads, Hobbi, Notify, Tuned, SoundBits, Audiohub, Venue, Collab, CatchUp, Moments, Mentions, Lasso…perhaps there is some truth to the urban legend: Meta cannot innovate! I knew a few of these attempts, but it was sobering to read how every single attempt by Meta to create the next big app failed miserably. The lone success is Messenger which didn’t even start as a standalone app. If I remember correctly, it was initially part of Facebook app, but they eventually forced you to download the Messenger app to access your DMs.

Reading their persistent failure, I was reminded of what Nikita Bier said on a podcast. He mentioned Meta has a very academic and scientific approach to growth, and it is incredible how much they have perfected the scaling game. But Meta struggles with creating that initial spark organically (I’m paraphrasing and writing from memory). Nikita’s subsequent success with “Gas” only further substantiated this speculation in my mind that Meta has a suboptimal approach to new standalone apps. It would be so much easier to fend off bear concerns of legacy apps (Facebook, Instagram) if Meta could just organically build a couple of other standalone apps organically and then let its “scientific” scaling game to take care of the rest.

A strategic error? While you did not allude to this, I wondered whether Meta’s decision to downgrade content from social graph to make space for content by recommendation engine beyond social graph in both Instagram and Facebook is a strategic mistake. Perhaps it would be better to maintain the supremacy of social graph on Facebook and use Instagram to capitalize on algorithmic content. I agree with you that there is very little true competition on social graph. I would go one step further: it is relatively easier for Meta to encroach into TikTok’s territory i.e. short-form video than anyone else to build a global, scaled social graph. Facebook and Instagram may be the only globally scaled social graph available for decades to come. Social graphs are likely to be more durable than anticipated and they are almost certainly more FCF generative businesses than apps purely optimizing for time spent which is inherently more competitive, fickle, and lower margin business.

A flawed mental model? Speaking of time spent, I suspect some investors are making a lot of erroneous assumptions about short-form video’s advertising dollar potential. Based on your data, I can see people spend less than half of the time on Instagram than they do on YouTube, but Instagram generated probably double the revenue of YouTube last year. Ad inventories/impressions, measurement, and attribution are all important variables that can get lost by investors who may think time spent as some form of panacea. In a post-ATT world, TikTok’s road ahead to scale their advertising infra will be fraught with challenges some seem to underestimate. That’s why I feel TikTok may be under pressure to attempt to build a social graph, the success of which is fairly uncertain. I share your skepticism on the scalability of TikTok’s current ad infra to make it to the big league (emphasis mine):

“Whereas a Facebook advertiser could grab some existing content from their product list page and turn that into an ad, a TikTok advertiser will have to find people to act in a video as well as make it worth watching so it doesn’t get skipped (if you do this well enough though, you don’t even need to pay for advertising as the algorithm can share your video with millions if its popular).”

The bold sentence makes me think short-form videos will create massive value for many businesses, but it may be a herculean task to capture that value by Meta and TikTok consistently.

Live and die by ROAS: One of my key takeaways from your piece is how Meta’s superior relative standing in terms of advertising infra among current set of competitors will not save it from the woes of the post-ATT world. Your case is convincing and now I think that my prior understanding on Meta’s relative standing being the dominant factor is flawed. Some key quotes from your piece:

“Whereas TikTok and Snapchat had some momentum with direct response, ATT was a formidable step back for them and it is questionable whether they will ever be able to close the AdTech gap in terms of targeting and measurement relative to Meta. However, while Meta might be in a better position relative to other platforms, but they are still net in a much worse position than pre-ATT.

Even though they may be relatively stronger than alternatives, it doesn’t matter because advertisers look at total return on ad spend, not relative return on ad spend (lose less money advertising with us will never be a great selling point).

...If a business cannot get an adequate return on ad spend, they usually can’t go elsewhere: it is just potential economic activity that is destroyed.”

Sorry, RoW: I am not sure I agree with your capex assumptions. Even in your optimistic scenario, you assumed 18% capex as % of revenue. I am going to make the case that it is, in fact, the pessimistic (albeit not improbable) scenario.

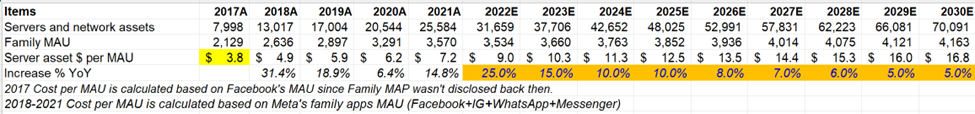

Meta’s Gross PP&E increased by ~$60 Bn in 2021 compared to its 2017 balance. But ~$30 Bn of it is quite discretionary and remnants of the bygone era (e.g. beautiful buildings, expensive office equipment etc.). As we enter a very different era for Meta, it is fair to say we are unlikely to see $30 Bn incremental spending on building and office equipment in the next 10-15 years (let alone 5 years). The much less discretionary expenses are servers and network assets which Meta continues to ramp up to cater to the increasing computing intensity of users consumption.

In 2021, Meta had ~$26 Bn servers and network assets which translate to $7.2 per MAU. If Meta adds another ~500-600 mn MAU in this decade and we keep the assumption that server/network asset per MAU will keep going up (see below), we may reach ~$70 Bn servers and network assets in 2030. It’s fair to say Meta’s capex is likely to be closer to maintenance capex in 2030, so I’ll focus on that to understand the long-term capex intensity of this business. While Meta currently amortizes these assets over 4 years, I am optimistic that they’ll realize similar benefits as Amazon and Microsoft did and will learn to lengthen the useful life to 5 years. Assuming 5 years useful life, depreciation for these assets is ~$14 Bn per year. If Meta becomes prudent in keeping their discretionary expenditure in check, depreciation for the rest of PP&E could easily be ~$3-5 Bn.

So, we may be looking at <$20 Bn maintenance capex. If ~$20 Bn is the maintenance capex, that leads to capex as % of sales of ~17% *today*. Therefore, even if we assume zero topline growth for Meta for this entire decade, Meta may still keep the terminal maintenance capex to be below 18% which you assumed. And if the topline grows, maintenance capex as % of sales will be much lower than 18%. That’s why I said, your best case scenario of 18% capex as % of sales is my worst case scenario.

A natural question may arise on whether the computing cost intensity will be even higher than I assumed. I assumed ~130% increase of computing cost intensity per user in 2030 (vs 2021). Could it be 200% increase? 300%? That seems unlikely to me. Not only computing cost may just get lot cheaper, but also there may be some interesting implication if computing intensity is indeed materially higher than modeled here. ARPU for Rest of the World (RoW) i.e. ex North America, Europe, APAC was just $12 in 2021. Therefore, if computing intensity keeps rising materially faster, it may be financially unfeasible for companies to serve those users. In such case, it may even be possible that Meta may not make certain features such as Reels available on these cost prohibitive countries.

Again, thank you for the very thoughtful work.

P.S. I also meant to include the following paragraph from Speedwell's piece (but later forgot) which I thought was fantastic to highlight why an effective and improving ad infra leads to a virtuous cycle of revenue growth for companies such as Meta:

...as targeting improves, (ad) inventory opens up, which first depresses prices, as auctions are less competitive. This lowers prices, which makes it even more attractive to advertisers, and more sellers allocate more ad budget to Facebook. Then the advertisers bid up the cost of impressions again and (hopefully) Meta releases new ad targeting improvements which start the cycle again, growing revenues with each iteration while maintaining happy advertisers.

Speedwell's response

1/ A big thank you to @borrowed_ideas for taking the time to read the entire report + provide such thoughtful feedback! Not easy to get through 160pgs in one day!

— Speedwell Research (@Speedwell_LLC) January 23, 2023

Cool to hear even someone covering the company for >5yrs learned some stuff :)

Some thoughts on his thoughts below https://t.co/cNfSLOY1sm

Here's the rest of that thread:

We think the “infrastructure as a moat” concept was probably more material pre-public cloud (Snapchat is run on AWS and Tiktok was on Alicloud prior to US data concerns).

The need for more content moderation (Meta has 40k moderators and highly advanced AI that can prevent a majority of unsavory content from ever being posted) and keeping up with a dizzying number of regulations could be a new sort of moat though.

Perhaps the content recommendation engine also becomes a competitive advantage, but it is curious they need to spend so much to improve recommendations whereas Tiktok hasn’t seemed to need to.

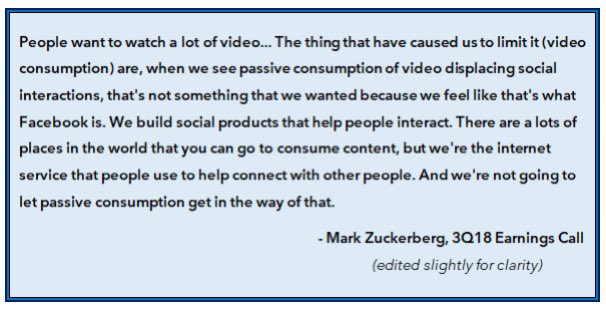

Agree on the potential for more recommended content to mess up their core “socializing job”. In theory, they could just revert the algo back if it wasn’t working/they saw another threat. In 2018 they deprioritized FB video in the feed because they felt it was displacing “meaningful” social interactions (created FB Watch tab). However, Reels is an admittance this sentiment was wrong and suggestive that FB tended to overvalue social graph content if anything.

Interesting point re: potential for capex intensity in RoW to increase beyond ARPU. The mitigating factor could be lower data consumption (FB Lite), but their ROI there could be worse. (To the extent a social network benefits from RoW, you can spin this as a competitive advantage)

The whole maintenance vs growth capex discussion for us is convoluted by the fact that ATT (and Google's future privacy actions) has (and potentially will further) degrade advertiser ROAS & attribution. So whether they are restoring lost signal or “improving” is debatable.

Since the server/AI spend is to get around the privacy actions and be able to do more with less, if they can’t get beyond their prior targeting capabilities then it could all be considered maintenance.

That’s probably too draconian of a reading and we think it is likely that this spend does yield incremental AI improvements as we are starting to see with their suite of Advantage Plus tools as well as with Reels recommendations.

Your $20bn maintenance capex figure seems reasonable to us.

Thanks again @borrowed_ideas. It was fun to trade notes! Also, some (only partially thought through) questions we’re chewing on having read your response:

How does influencer leverage change when more content is recommended? Is “reach” devalued and does “endorsement” become more meaningful? (Maybe less views w/ higher conversions?)

What does the prominence of Amazon Shops mean for Instagram Shops? (And more perplexingly, why did Instagram enable that ability to add links to Stories just recently–what changed?)

What if AI eventually generates the content (as is all the range in SV with OpenAI and generative AI)

Why pay for ads if you can make compelling content that gets shared for free? Does this mean de facto that ads will be more intrusive as only those who can’t make good content pay for ads?

My follow-up to Speedwell

Irrelevance of infra moat in the age of Public Cloud: That is a very good rule of thumb. But there can be some very good exceptions and I suspect a global, scaled, hyper-personalized, and extremely compute intensive services such as Meta/TikTok is one of those exceptions. Let me quote Ben Thompson to make this point:

“The problem for Snap is that to the extent that AI capabilities become critical not only for content but also advertising the greater the burden their reliance on cloud providers will become. To put it another way, while I am generally a huge advocate of using public clouds — the flexibility, scalability, and engineering focus it enables is almost always worth the higher cost — there may be an exception for companies that are extremely AI-dependent, and there is a strong argument that this is exactly where “social networks” (I put that in quotes because the entire point is that reality is moving beyond social networks) are headed.”

Also note that if Meta does a really good job at managing their infra investments as well as Public Cloud, they’ll save the margins Public Clouds will be making on serving TikTok. WSJ reported TikTok’s Gross Margin was ~56% in 2021. Assuming that’s true, there are probably multiple potential rationales of such Gross Margin:

a) the platform’s monetization is far from fine-tuned, and they are far from monetizing the time spent to translate to advertising dollars. Margin will improve as monetization improves but cost of revenue grows at a lot slower pace,

b) short-form video is a materially lower gross margin business compared to text and image based feeds and even terminal economics is no where close to high 80s Gross Margin that Meta enjoyed a few years back, and

c) it is expensive and inefficient to build such a globally scaled platform on public cloud who are obviously happy to make money hand over fist over your usage.

My guess is all three rationales are in play in varying degrees here and while the infra as a moat has certainly narrowed over the last two decades thanks to public cloud, it is not fully eliminated.

Content moderation/regulation as a moat: This is also a good rule of thumb, and as a shareholder, while I would love to have this moat, I suspect it is not much of a barrier for startups. Would regulators really go after “Clubhouse” (just an example) if we find terrible content are being posted on that platform? I doubt it. Regulators are more likely to put a blind eye on up-and-coming social apps as they probably know any draconian regulation would simply lead to death for those new apps. Meta, on the other hand, makes ~40-50% operating margin on Family of Apps (FOA) and is almost indiscriminately hated by both sides of the political aisle. There’s a lot more to gain by regulators, politicians, and media companies by reporting unsavory details about Meta. A dying “Clubhouse”? Not so much.

But let’s focus a little more on TikTok since they’re probably going to be in the same bucket as Meta these days. They too are increasingly universally hated by regulators, politicians, and other media companies. Can they beef up their moderating team as much as Meta? They probably wouldn’t be able to if they were under pressure from their shareholders to make money. However, it does seem they have the license from their shareholders to not necessarily focus on profitability. Ah, the joys of being a private company! If this “joy” proves to be short-lived (likely scenario), in such case, I agree that this would indeed be a moat by Meta against TikTok.

Is Reels a retreat from “Meaningful Social Interaction” (MSI)? You mentioned “in 2018 they deprioritized FB video in the feed because they felt it was displacing “meaningful” social interactions (created FB Watch tab). However, Reels is an admittance this sentiment was wrong and suggestive that FB tended to overvalue social graph content if anything.”

I don’t necessarily think Reels is a massive retreat from MSI. While “FB Watch” was mostly about passive consumption, Reels is a more eclectic mix of passive consumption and MSI. In 3Q’22, Meta mentioned 1 Bn Reels was shared via DMs on IG *everyday*. Clearly, Reels leads to more sharing and interactions among friends/followers than “Watch” did. In fact, such trend is perhaps one of the key reasons Zuckerberg wants to heavily lean onto short-form video after some initial skepticism.

Having said that, as mentioned in my earlier comments, I do have mixed feelings about the mix of content from social graph and recommendation engine based algorithmic content. I wonder whether they should favor the mix of content from social graph heavily in either Facebook or Instagram to maintain their value proposition of social graph strongly. I’m not too worried since this seems to be, as Bezos would say, a “two-way door” decision. Meta will eventually end up where the data says they should end up.

You left some thought provoking questions at the end that I need to mull over more to organize my thoughts. I suspect I may not have much of an answer to a couple of questions. In any case, I enjoyed this back and forth with you, and hope to follow your work closely going forward.

Thank you for reading!